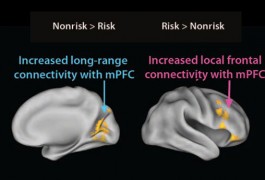

Risk gene for autism rewires the brain

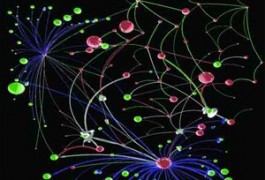

A variant of the autism risk gene CNTNAP2 may alter the brain to emphasize connections between nearby regions and diminish those between more distant ones, according to a study published 3 November in Science Translational Medicine.