Flu triggers schizophrenia-like features in monkeys

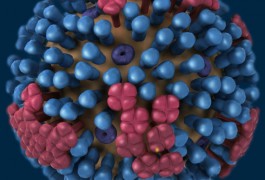

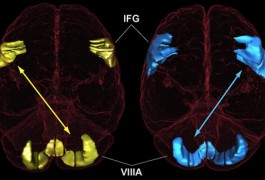

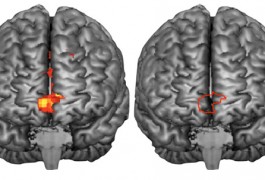

Babies born to rhesus monkeys infected with the flu virus during pregnancy have significantly smaller brains than normal, and other brain abnormalities seen in schizophrenia, researchers have found. The study, published last month in Biological Psychiatry, provides the first evidence in non-human primates linking flu infection to a higher risk of schizophrenia.