Mouse models for autism debut

Two research groups have achieved an elusive goal: producing mouse models that show distinct social and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of autism.

Autism’s core symptoms accompany a constellation of subtle signs that scientists are just beginning to unmask.

Two research groups have achieved an elusive goal: producing mouse models that show distinct social and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of autism.

People with autism struggle to see their own role in social situations. That’s the conclusion from the first study to scan individualsʼ brains while they interact with another person – a technique that could lead to a diagnostic tool.

As many as one in every three people with autism develop a macrocephalus, or extremely enlarged head, at some point in their lives, an observation largely accepted as fact. But how or why this happens ― and whether it happens consistently enough to be useful in diagnosing autism ― remains contentious.

Imagine being confined for at least half an hour to a dark, claustrophobic tunnel, in a machine so obnoxiously loud that it sounds like you’re in an oil drum with a jackhammer pounding on the outside. Thatʼs whatʼs involved in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): an experience enough to make even the bravest among us flinch.

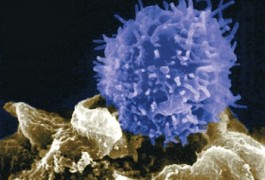

A new genetic study is lending support to the notion that immune system abnormalities and some forms of autism go hand in hand.

Itʼs not often that movies, books and plays represent science accurately, or with a true and empathetic understanding of its complexity.

Huda Zoghbi and her colleagues painstakingly sequenced the candidate genes for Rett syndrome, culminating in the 1999 Nature Genetics report that pinpointed six de novo mutations in the MeCP2 gene as the cause of the disorder.

Fragile X syndrome is a rare and devastating condition, and a risk factor for autism. New research suggesting the condition is reversible in mice has some wondering whether treatments for the syndrome ― and for some forms of autism ― could be on the horizon.

In 1982, Josh Huang was an impressionable young biology undergraduate at Shanghaiʼs FuDan University. Like some of his fellow Chinese students, he knew he wanted to be a neuroscientist, but with limited access to scientific journals, had no idea which big questions were then at the forefront of research.

Gray matter, that mysterious brain substance, is thought to control everything from motor function to mental acuity. In recent years several studies have suggested that an excess of gray matter during childhood is to blame for the symptoms of autism.