THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

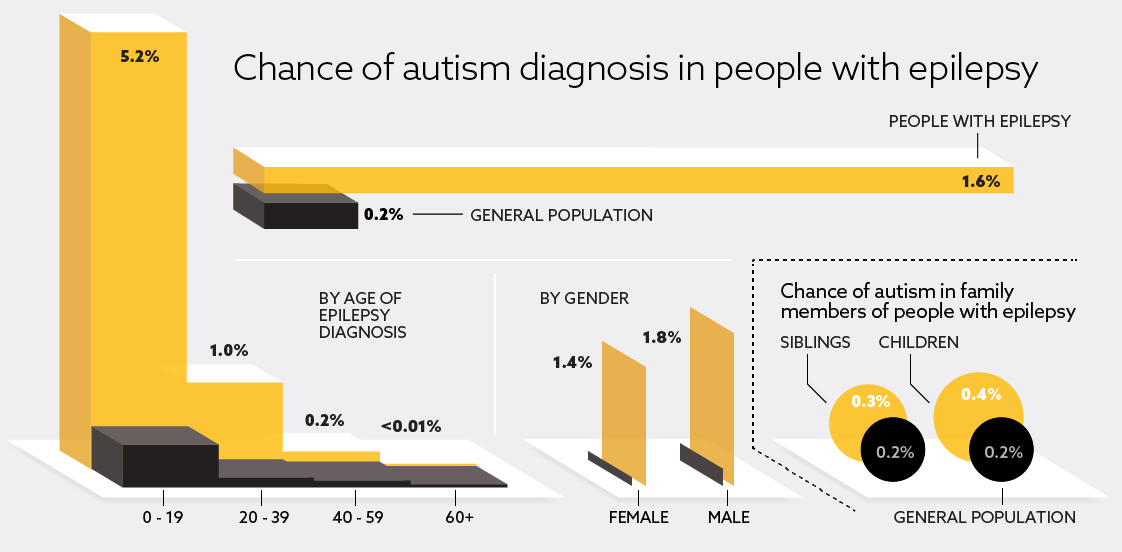

About one in three people with autism also have epilepsy. A study of 690,000 people in Sweden quantifies the risk in the opposite direction. People with epilepsy are at eight times the risk of autism as the general population (see graphic below). Siblings and children of individuals with epilepsy are also at an increased risk1.

The findings, which appeared in June in Neurology, lend credence to the idea that autism and epilepsy share genetic roots. Among some individuals with epilepsy and their relatives, a second genetic ‘hit’ or environmental trigger may tip the balance toward autism.

“The core mechanisms behind epilepsy and autism are probably close or similar, and there are most likely different factors bringing an individual to a tipping point where one or both disorders develop,” says lead researcher Heléne Sundelin, senior neuropediatric researcher at Linköping University Hospital in Sweden.

Researchers have tried to parse the epilepsy-autism connection before. The new study’s sample size adds power to the genetic hypothesis, says Alyssa Rosen, a pediatric neurologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study. “Large, population-based studies such as this one are hard to come by.”

But the study’s approach also has drawbacks, Rosen says. The researchers relied on medical records rather than confirming each autism diagnosis, so some people may have been wrongly diagnosed with autism, and some with the condition may have been missed. Such inconsistencies could skew the estimates of autism risk, she says.

“[The study] does not, in my opinion, allow for a way to confidently estimate the risk of autism in people with epilepsy and their family members,” Rosen says.

Record request:

Sundelin’s team identified 85,201 individuals with epilepsy from Sweden’s National Patient Registry, which includes information from all hospital visits in the country. About 1.6 percent of these individuals also received an autism diagnosis.

They then combed the records of 80,511 siblings and 98,534 children of these individuals with epilepsy — excluding anyone who had epilepsy themselves — for autism diagnoses. They compared each family of a person who has epilepsy with five families that have no history of seizures.

Their analysis confirmed previous reports that people with epilepsy have an elevated risk of autism. What’s more, their siblings are at 1.5 times the risk of autism as the general population, and their children have double the risk.

This increased risk may be biological — shared genetic risk factors for the two conditions — or even sociological.

A person diagnosed with epilepsy is likely to get a lot of clinical attention — raising the likelihood of an autism diagnosis, says Sarah Spence, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the work.

But family members without epilepsy aren’t subject to the same scrutiny. So their increased autism risk is best explained by shared genetic mechanisms, Spence says.

Gender effects:

The chances of receiving an autism diagnosis are especially high among people whose epilepsy is flagged in childhood. Compared with these individuals, autism risk is 1.5 times lower in people diagnosed with epilepsy after age 20, and 6 times lower after age 60.

The researchers also found that a child is at a higher risk of autism when it’s her mother, rather than her father, who has epilepsy. Exposures in the womb, such as to the seizure medication valproic acid, may raise the risk of autism in children, says Orrin Devinsky, director of the New York University Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, who was not involved in the study.

Boys and men with epilepsy are slightly more likely to receive an autism diagnosis than girls and women with the condition, the researchers found. These results are consistent with reports that autism is more common in boys than in girls.

The researchers did not include information about the participants’ intelligence, which may play a key role in the autism-epilepsy connection, Rosen says. People with autism and low intelligence have a particularly elevated risk of seizures.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.