1985 paper on the theory of mind

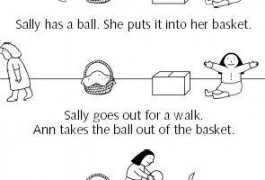

In 1985, Simon Baron-Cohen, Alan Leslie and Uta Frith reported for the first time that children with autism systematically fail the false belief task.

Diagnosing autism is an evolving science but a crucial first step to understanding the disorder.

In 1985, Simon Baron-Cohen, Alan Leslie and Uta Frith reported for the first time that children with autism systematically fail the false belief task.

Sitting on a sofa in his office at the Yale Child Study Center, Ami Klin plays a movie clip on a tiny laptop. The clip stars a younger Klin, with larger glasses but the same easy smile, vying for the attention of a young girl with autism. His face inches from hers, he speaks in a warm, animated voice. But the girl never looks from the toy blocks in her hands. Suddenly, she spots an orange M&M in the far corner of the room and scoots after it.

In the past two weeks, autism researchers and advocacy groups have been agog with news that autism could be linked to an extremely rare group of metabolic diseases.

Autism is caused by poor parenting, particularly by ‘frigid’ mothers who reject their children. Such a statement would seem bizarre today. But 30 years ago parents, especially mothers, were blamed for their childrenʼs autism. But then in 1977, one study, published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, single-handedly turned the field around to recognize the importance of genetics.

Two research groups have achieved an elusive goal: producing mouse models that show distinct social and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of autism.

People with autism struggle to see their own role in social situations. That’s the conclusion from the first study to scan individualsʼ brains while they interact with another person – a technique that could lead to a diagnostic tool.

As many as one in every three people with autism develop a macrocephalus, or extremely enlarged head, at some point in their lives, an observation largely accepted as fact. But how or why this happens ― and whether it happens consistently enough to be useful in diagnosing autism ― remains contentious.

Itʼs not often that movies, books and plays represent science accurately, or with a true and empathetic understanding of its complexity.

Donald T. was not like other 5-year-old boys. Leo Kanner knew that the moment he read the 33-page letter from Donaldʼs father that described the boy in obsessive detail as “happiest when he was alone… drawing into a shell and living within himself… oblivious to everything around him.”