THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

True to its dubious moniker as the ‘trust hormone,’ oxytocin promotes cooperation among monkeys working toward a reward. Unexpectedly, though, it may make monkeys less interested in others’ actions and more focused on their own, according to unpublished results presented yesterday at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago.

The study is the first to look at oxytocin’s effect on individual neurons while monkeys interact. The results highlight how little researchers know about its impact in the brain and offer a note of caution about its use in children with autism, says Keren Haroush, instructor in neurosurgery and a postdoctoral fellow in Ziv Williams’ lab at Harvard Medical School, who presented the findings. “It’s not known how oxytocin affects brain development when given on a regular basis.”

The work follows from a study published earlier this year in which the same team found that rhesus macaques have a set of neurons whose primary function is to predict others’ actions1. These neurons are in the anterior cingulate cortex, a brain region involved in reward and decision-making.

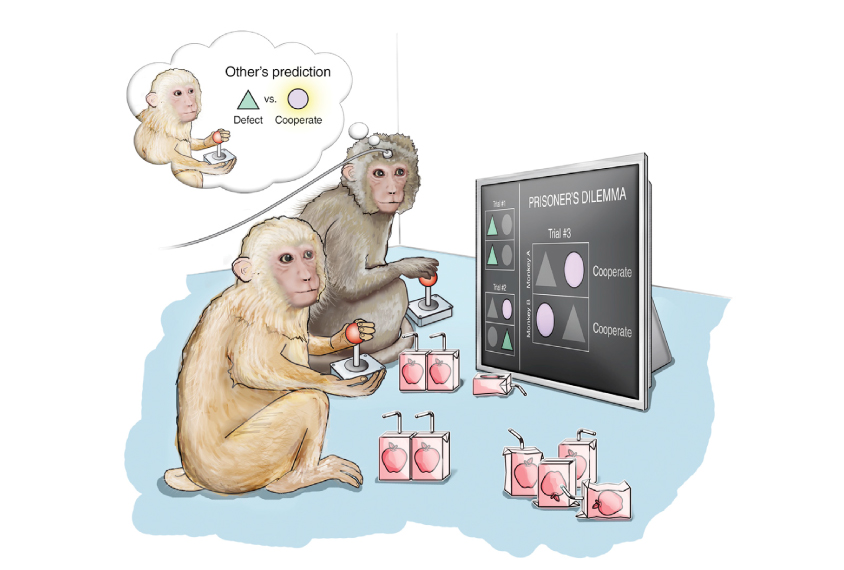

The researchers trained monkeys to participate in a modified version of ‘the prisoner’s dilemma’ — a classic game that pits the desire for self-gain against an instinct toward mutual benefit. In this version, two monkeys face their own screen and have the option to either ‘cooperate’ or ‘defect’ by choosing an orange circle or a blue triangle. Depending on the actions of the other monkey, this decision yields them a certain amount of juice.

For example, if both monkeys opt to cooperate, they each get four drops of juice, and if they both defect, they get two drops each. A monkey wins the most juice if it defects when its partner cooperates, earning six drops to its hapless partner’s one. However, the monkeys see each other’s choices after they pick — and hear their partner enjoying the juice. A monkey that has been cheated of juice may feel less likely to cooperate in the future.

Mutual gain:

When a computer plays the game, it eventually makes the most logical choice, which is to defect every time. But about half the people who play the game choose to cooperate, a tendency that may indicate our natural social inclinations.

In the new study, Haroush and her colleagues found that monkeys behave like people do, choosing to cooperate about 35 percent of the time. If a monkey’s partner has cooperated in the previous trial, it reciprocates this gesture 62 percent of the time. This tendency to cooperate is substantially lower if the monkeys are kept in separate rooms, or are playing with a computer.

The researchers also performed the experiment while measuring the activity of nearly 400 individual neurons in the brains of two monkeys. One-quarter of the neurons are specific to the choice to either cooperate or defect.

Interestingly, another one-third of the active neurons seem to correspond not to the choice the monkey itself makes, but rather to what it thinks another monkey is likely to do. The activity of these neurons successfully predicts the other monkey’s choice about 80 percent of the time.

The researchers gave the monkeys intranasal oxytocin and compared the animals’ choices before and after the hormone boost. In people, oxytocin increases the tendency to cooperate2. Likewise, the monkeys were 25 percent more likely to cooperate after they had sniffed oxytocin than before. This tendency went away when the monkeys were in separate rooms, indicating that it is a social effect.

More neurons in the anterior cingulate cortex fire specifically during cooperation, rather than during defection, after inhaling oxytocin. But surprisingly, these neurons are engaged only when a monkey is making its own decision. In fact, the monkeys had fewer neurons dedicated to predicting others’ actions.

“[This is a] major, major reorganization of selectivity properties,” says Haroush. “It’s very clear that the monkeys are more interested in encoding their own decision rather than [predicting others’ actions.]”

These findings may explain why the so-called ‘love hormone’ fosters some distinctly unloving behaviors. For example, a 2010 study suggested that oxytocin may promote distrust toward people perceived as outsiders3.

For more reports from the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.