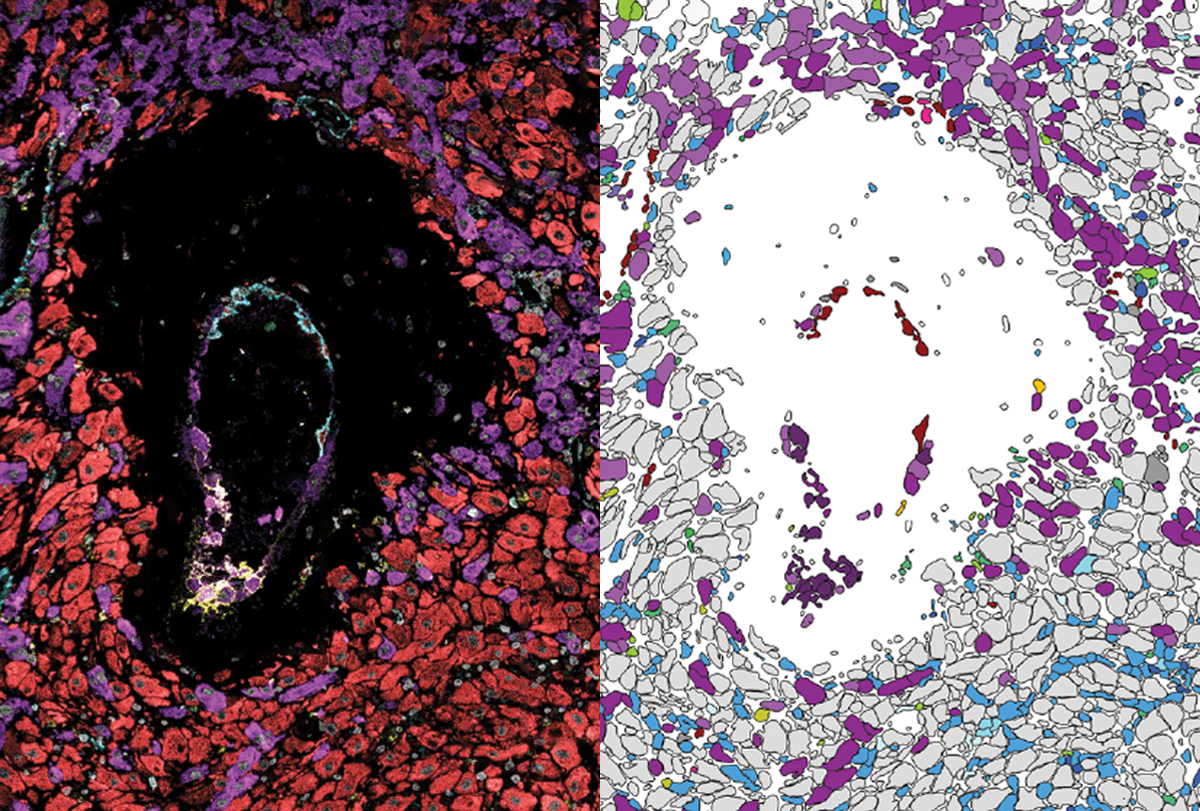

A new resource maps the cells of the human placenta and uterus between 6 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, giving an unparalleled look at how fetal cells invade the uterine wall and remodel maternal blood vessels to access nutrients.

The atlas also shows the typical changes in maternal immune cells that enable a pregnant person to tolerate the presence of the fetus, despite its different genetic makeup. Atypical activation of maternal-immune responses in early pregnancy may disrupt fetal brain development and is linked to autism.

By showing how typical early pregnancy unfolds at the single-cell level, the map could help inform future studies of how the process may differ in conditions such as autism, says lead investigator Michael Angelo, assistant professor of pathology at Stanford University in California.

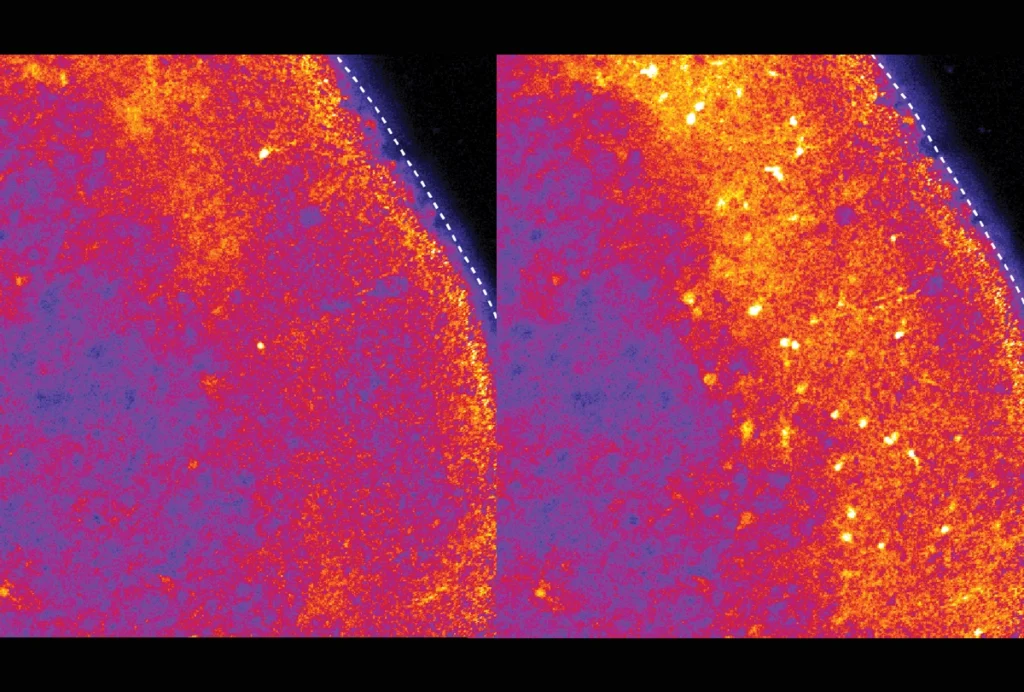

During pregnancy, cells called trophoblasts on the fetal side of the placenta invade the decidua, the tissue lining in the uterus, and remodel the mother’s spiral arteries. The arteries get bigger, enabling the fetus to receive nutrients and oxygen and get rid of waste.

This process involves dramatic changes in blood flow to the uterus and in maternal immune responses to proteins produced by the fetus, Angelo says. Insufficient remodeling may lead to preeclampsia, which is linked to autism.

The remodeling process is more invasive in people than in animals, and the new work could enable researchers to glean further insights about the similarities and differences, Angelo says. “There’s going to be a lot more discussion about trying to triage when animal models are appropriate or not.”

A

Most of the samples came from Caucasian women, but some came from African-American, Hispanic and Asian women. The work is part of an ongoing project called the Human BioMolecular Atlas Program (HuBMAP), which is creating spatial maps of individual cells across many organs and detailing the cells’ patterns of gene expression and protein production.

The number of maternal immune and stromal cells present in the samples, and their gene expression patterns, vary with gestational age, Angelo and his colleagues found. Some cell types were present early in pregnancy but declined over time, whereas others increased in number as the fetus developed.

“What’s normal at 6 weeks may not be normal at 20 weeks,” Angelo says.

In fact, by analyzing the number and proportion of immune cells in the decidua, the team was able to predict the samples’ gestational ages within 19 days. Angelo and his colleagues published their findings last week in Nature.

The placenta cell map is available on an open-access data platform, along with cell atlases for other organs studied in the HuBMAP project.

T

“It’s another building block to understand these very, very early stages of placental invasion,” Penn says.

The work expands what is known about artery remodeling during early pregnancy and could help scientists understand how preeclampsia and other conditions affect this process at the level of cells and tissues, says Alexandre Bonnin, associate professor of physiology and neuroscience at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study.

“This is an important step forward,” Bonnin says.

Angelo’s team plans to look at the cellular changes associated with preeclampsia, which occurs in about 5 to 8 percent of pregnancies in the United States. The team would also like to look at how pregnancy affects immunity overall, Angelo says.