Sounding out ultrasounds; name game; geek gathering

A tie between first-trimester ultrasounds and autism severity is tenuous at best, misnamed genes litter the literature, and neuroscientists enjoy their version of summer camp.

- New findings link first-trimester ultrasounds with autism severity in boys who also have a genetic anomaly associated with the condition. But the study, published 1 September in Autism Research, has attracted criticism.

The researchers analyzed data from 111 boys who have autism and DNA duplications or deletions called copy number variations (CNVs), along with their mothers. (The data came from the Simons Simplex Collection, an autism registry funded by the Simons Foundation, Spectrum’s parent organization.)

The team looked for any association between autism features and having an ultrasound during the first trimester of pregnancy. They found that the boys who were exposed to an ultrasound in the first trimester had a lower nonverbal intelligence quotient score and more repetitive behaviors than those whose mothers did not get an early ultrasound.

Doctors perform ultrasounds routinely in the second trimester to monitor fetal growth and determine the date of conception. Randomized trials have revealed no significant risk to the fetus from the scan. Doctors may prescribe ultrasounds in the first trimester if they see signs of a problem, such as an ectopic pregnancy.

But the new study does not actually show that having a first-trimester ultrasound raises the risk of severe autism features in a child, writes journalist and biologist Emily Willingham in Forbes.

For one, the findings are inconsistent. For instance, the researchers also find a connection between first-trimester ultrasounds and milder social problems in a larger sample of children with autism.

In addition, the researchers lumped together children with CNVs across a variety of chromosomes. This heterogeneity undercuts the findings, Willingham writes.

- A group of leading U.S. neuroscientists is set to meet on 19 September to discuss a global effort to tackle three “three grand challenges for brain science” that they think can be solved in the next 10 years, according to a 31 August story in Technology Review.

Members of the group include geneticist George Church of Harvard University and Story Landis, former director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

The challenges are mapping variations in brain structure across species from zebrafish to marmosets; modeling how the brain solves complex computational problems such as recognizing emotions and navigating a bumpy sidewalk; and diagnosing, treating and preventing brain disease.

The vision also includes cloud-based computer software that neuroscientists can use to collect, store and analyze their data.

- Microsoft Excel does not excel at naming genes. For example, its default settings tend to convert certain names to dates — SEPT2, for example, might become 2-Sep.

Researchers identified the problem more than a decade ago. But the naming mistakes persist in spreadsheets that accompany papers published in the past 10 years, most frequently in the past five. One-fifth of the spreadsheets supplementing papers in 18 journals, including Science, Nature and PLoS ONE, contain the erroneous monikers, write Assam El-Osta and his colleagues in the 23 August issue of Genome Biology.

Some of the errors even crop up in the first few lines of the files.

The researchers downloaded and searched 35,175 supplementary spreadsheets associated with 3,597 papers for official gene symbols. They manually confirmed errors that fell out from the electronic search.

Reviewers and editorial staffers at journals can prevent the errors by copying and pasting a file’s full column of gene names into a new spreadsheet and sorting them. Gene symbols that the software has converted to dates appear at the top of the list by default, and can then be corrected.

The researchers are also willing to share the software they used to screen for the errors.

- A low dose of the antidepressant sertraline (Zoloft) improves language skills in children with both autism and fragile X syndrome, according to a 24 August study in the Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics.

Fragile X syndrome is the most common form of inherited intellectual disability and single-gene cause of autism. Nearly one-third of people with fragile X syndrome have autism features.

The researchers gave sertraline to 27 children with fragile X syndrome, ages 2 to 6, for six months. Another 30 children with the condition received a placebo. More than half of the children also had autism.

In all of the children, the drug improved visual perception, fine motor skills, social participation and overall development. But only the 15 treated children who have both fragile X and autism showed improved language ability.

- Neuroscientists gathered this week at the University of Washington eScience Institute for a hands-on workshop on neuroimaging and data science.

‘Neurohackweek’ was inspired by a similar assembly of astrophysicists called AstroHackWeek. It featured lectures and workshops on technologies for analyzing, sharing and reproducing neuroscience data and findings.

Featured speakers included science communicator Terri Gilbert of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle and Russell Poldrack, a psychology professor at Stanford University in California who climbed onto a magnetic resonance imaging bed two or three times weekly for a year to generate what, at the time, was the most detailed record of an individual’s brain.

Participants posted videos of the proceedings on the event’s Twitter feed.

- Making a career move? Send your news to [email protected].

Explore more from The Transmitter

Cocaine, morphine commandeer neurons normally activated by food, water in mice

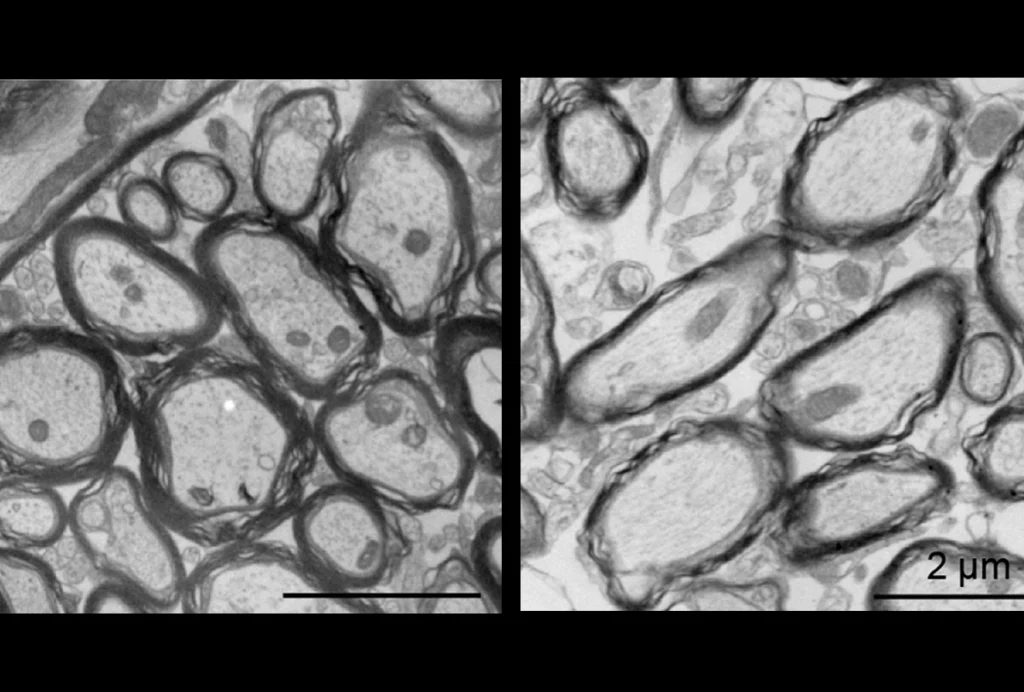

X chromosome inactivation; motor difficulties in 16p11.2 duplication and deletion; oligodendroglia