Excitatory neurons in a thin strip of the thalamus fire when a mouse first encounters another mouse but not when it sees a toy mouse, a new study has found.

The neurons fire less with each subsequent encounter, hinting at a role in social recognition, the process through which social interactions feel novel at first and grow familiar over time.

The findings, published 26 May in Biological Psychiatry, are the latest to implicate a discrete group of thalamic neurons in a specific aspect of social behavior.

“The more specific we get in our understanding of the circuits or cell populations that are involved in specific behaviors, the better we can get at targeting these behaviors,” says lead investigator Hala Harony-Nicolas, associate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience and a fellow at the Seaver Autism Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

The thalamus, a deep brain structure that serves as a hub for sensory inputs and projects out to multiple brain regions, is emerging as a key regulator of social behavior and a prime target for autism therapies.

“In order to realize the potential of circuit-based therapies, we’re going to want to be as specific as possible,” says Audrey Brumback, assistant professor of neurology and pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin. “I think this study is just one chapter in the catalog of thalamic neurons and how they encode information related to social behavior.”

The new mouse study adds detail to a once-fuzzy picture of the thalamus, says Antonio Hardan, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California. Hardan was not involved with the study but has been using brain imaging to study the thalamus in people for more than 20 years. “In human studies, we look at the thalamus in general. Here, they’re looking at a small part of thalamus, which is much more granular,” he says.

H

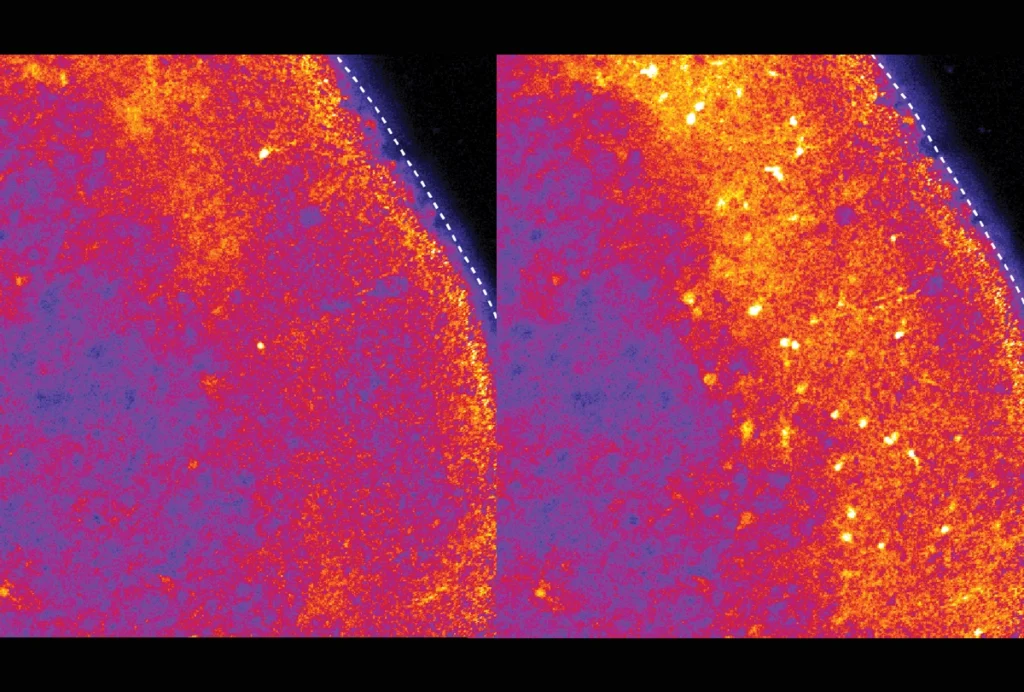

The researchers placed an adult mouse in a box for one hour with either an unfamiliar same-sex juvenile mouse, a toy mouse or nothing. Mice exposed to another mouse had more active neurons in the posterior intralaminar complex than those exposed to a toy mouse or no stimulus, the researchers found when they looked for a marker of neuronal activation in brain slices. The active neurons communicated with the neurotransmitter glutamate.

When adult mice roamed a cage with two chambers — one empty and the other containing either a same-sex juvenile mouse, an opposite-sex adult mouse or a toy mouse — they spent more time exploring the area near another mouse than the empty chamber but showed no such preference for the toy mouse. Neuronal activity increased during interactions with another mouse but not during those with the toy, according to recordings of electric signals from excitatory neurons in the posterior intralaminar complex.

This subset of neurons was most active during an initial encounter with another mouse. The amount of firing dropped off as the number of encounters with the same mouse increased.

Chemically inhibiting the neurons had no effect on the mouse’s preference for another mouse versus an empty chamber, further experiments showed. But in female mice, inhibition lengthened the time it took for the novelty of the interaction to wear off: The mice spent about the same amount of time interacting with a familiar mouse as they did when the encounter was novel.

“Usually, you see a decrease in interaction, meaning there is recognition,” Harony-Nicolas says. “With inhibition, that was not the case.”

Male mice did not show a decrease in interaction with inhibition or a placebo treatment.

The findings point to a role for glutamatergic neurons in the posterior intralaminar complex in social recognition but not in other aspects of social behavior, such as social motivation.

“This study is music to my ears,” says Hardan, who previously identified social recognition as one of five domains of social cognition and behavior. “It’s linking a specific behavior to a specific brain region and a specific neurotransmitter system.”

Social difficulties are a core trait of autism, but the nature of those difficulties may vary across individuals, Harony-Nicolas says: Some autistic people may have trouble initiating social interactions, whereas others find it hard to maintain those interactions. “Given the heterogeneity, I think it is very important to parse out the different parts of social behavior,” she says.

Harony-Nicolas and her team plan to test the effects of SHANK3 and other autism-related mutations on social behavior and activity in the posterior intralaminar complex.