Maternal immune response dulls male rats’ social radar

Male rats prenatally exposed to a maternal immune response have atypical responses to other rats in distress, according to a new study.

When a person’s immune system detects a foreign pathogen, a cascade of inflammatory signaling molecules calls the body’s immune cells to action. If the infected person is pregnant, their growing fetus may be exposed to those signaling molecules, which some research suggests can alter brain development and increase the likelihood of conditions such as autism.

In rodents, such exposure also shapes sensitivity to certain social cues, according to a new study. Unlike wildtype animals, the findings reveal, male rats whose mothers were treated with a mock virus during pregnancy to prompt an immune response did not change their social interactions with a stressed animal.

“What this suggests is that there’s a breadth of neurobiological processes that are affected by risk factors like immune challenges, like illness, like stress,” says lead researcher John Christianson, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Boston College in Massachusetts.

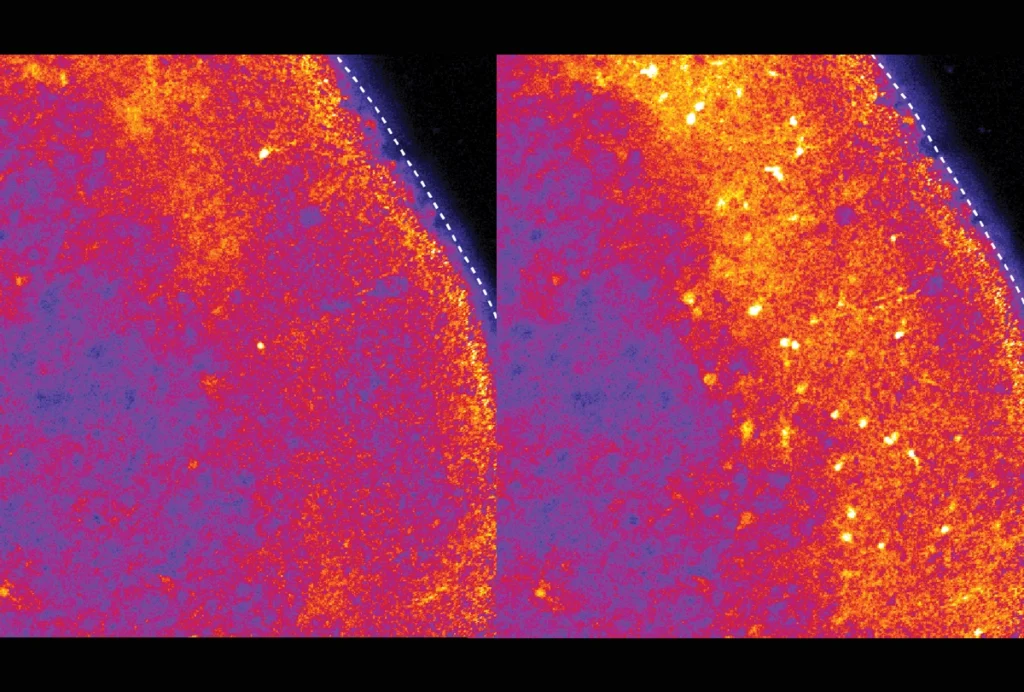

The treatment also affected the neurons in the male rats’ insula — a brain region known to process social information and integrate signals about one’s own body with external cues. After prenatal exposure to maternal immune activation, the male rats’ insular neurons became less sensitive to the release of a stress hormone, the study shows.

That points to stress responsiveness as a potential factor underlying atypical social behaviors, says Jared Schwartzer, director of the Science Center and associate professor of psychology and education at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts, who was not involved in the study.

But the findings are preliminary and need to be replicated, Schwartzer says, particularly because the team evaluated only one or two pups from each litter. That tactic does partly control for similarities among littermates, but “there’s a random selection happening there,” he says. “What if they’re missing out on other measurements in the rest of the litter?” Instead, collecting data from the full litter and statistically controlling for the so-called ‘litter effect’ — the natural variability that exists between different litters of mice — would better eliminate that uncertainty, he says.

C

The rats, Christianson says, seem to consider stressed adults, but not stressed juveniles, a potential threat. “We were sort of floored,” he says, because the results modeled how he thought a person might react in a similar situation.

In the new study, the researchers injected pregnant rats with the compound poly I:C, which mimics an infection, and then tested their pups on the same task once they reached adulthood. Female rats that had been prenatally exposed to their mother’s immune response performed typically, the team found, but their male counterparts did not differentiate between stressed and non-stressed animals of any age.

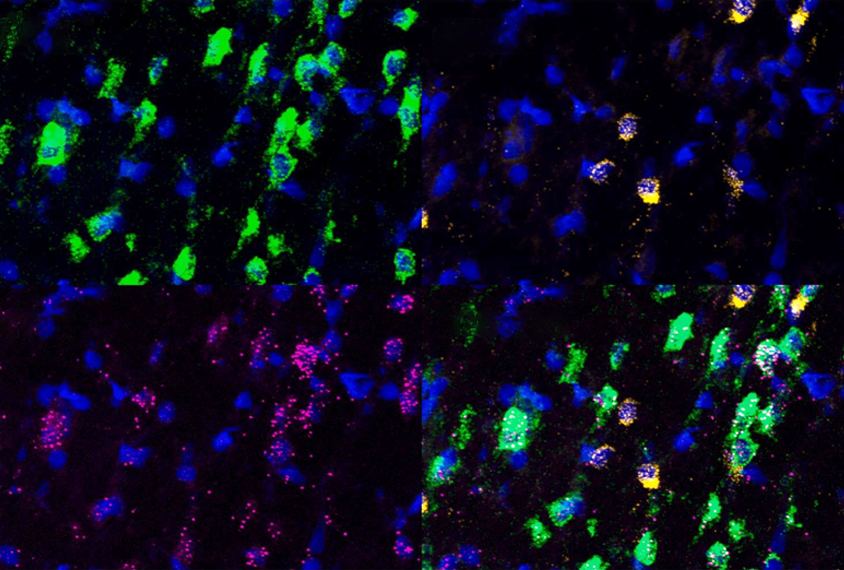

For wildtype male rats, this social behavior requires neuronal signaling from the insula, according to past work from Christianson and his team. When the animals are exposed to a stressed rat, the insula receives a flood of the stress hormone corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), which activates neurons in the insula and boosts rats’ interest in social behavior. Female wildtype rats, like males, tend to a stressed juvenile rat and avoid a stressed adult rat, but they do not have the same insular sensitivity to CRF.

When male rats had a prenatal exposure to maternal immune activation, however, their insular neurons’ sensitivity to CRF disappeared, tests of the animals’ cortical slices revealed. The number of CRF receptors in the insula remained stable, suggesting that “something else is happening,” says study investigator Nathan Rieger, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Neurons from the insulae of female rats, on the other hand, showed an increased sensitivity to CRF, which may reflect some sort of protective effect in the female animals, Rieger says.

The work was published in January in Hormones and Behavior.

O

It may be that these social behaviors differ between mice and rats, Christianson says. It is also possible that he and his colleagues saw a more specific effect because they used a relatively small dose of poly I:C.

The makeup of poly I:C is something the field should consider, Schwartzer says. Poly I:C is “a messy compound,” he says, and researchers are finding that it contains other immune-stimulating factors in it that can differ from batch to batch. “Each lab might be stimulating the immune system in a unique way,” he says, which could explain the variable responses.

Moving forward, it will also be important to investigate the relationship between CRF sensitivity and the treated animals’ atypical social behavior, says Kathryn Lenz, associate professor of behavioral neuroscience at Ohio State University in Columbus, who was not involved in the work.

“This is just a first step,” Lenz says. “Future studies are needed to really show that CRF is causing this to occur.” Still, she says, “it’s exciting to imagine that it could possibly be playing a role.”

Christianson agrees that more work is needed to establish that link. “Why the males became less sensitive to [CRF] is still enigmatic,” he says. “It just happens to be consistent with what happens to people when they have deficits in social cognition.”

Explore more from The Transmitter

RNA drug corrects calcium signaling in chimeric model of Timothy syndrome