Clusters of human cells take root in rat brains

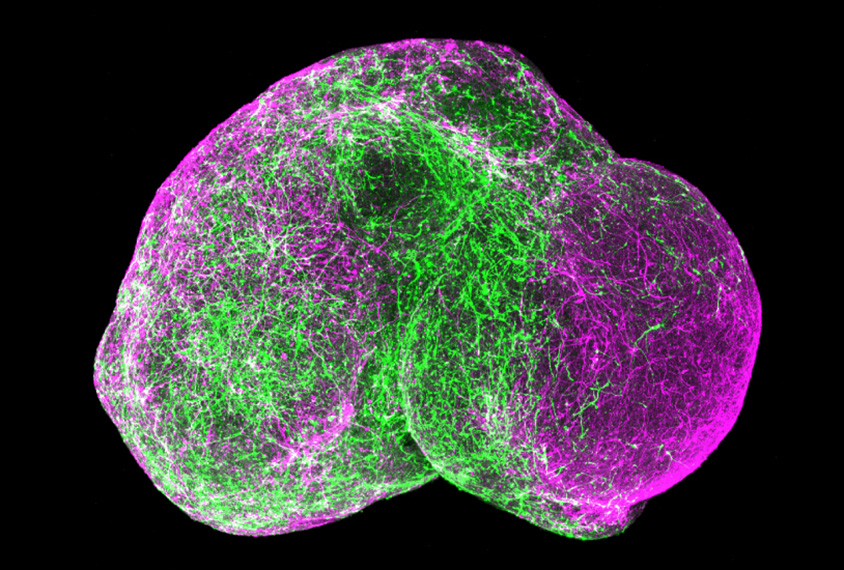

Balls of human neurons transplanted into a rat brain receive blood supply and connect with neural circuits.

Balls of human brain cells transplanted into a rat brain receive a blood supply and connect with neural circuits.

Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2018 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, California.

Brain organoids derived from human cells and maintained in culture enable scientists to study the brain in a three-dimensional model. However, they do not receive a blood supply, nor do they make active connections with other neurons in long-range circuits.

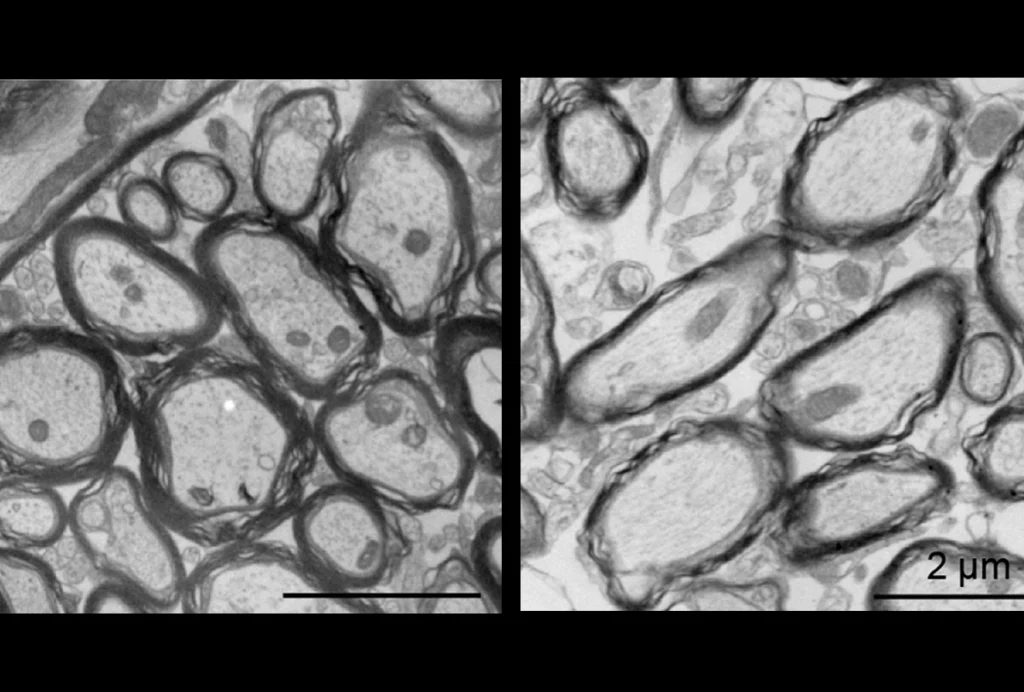

In the new work, researchers introduced human organoids into the sensory cortex of 5-day-old rats. Within 30 days, the human cells had made connections with neural circuits, as well as with the rats’ immune cells, or microglia, and their support cells, called astrocytes.

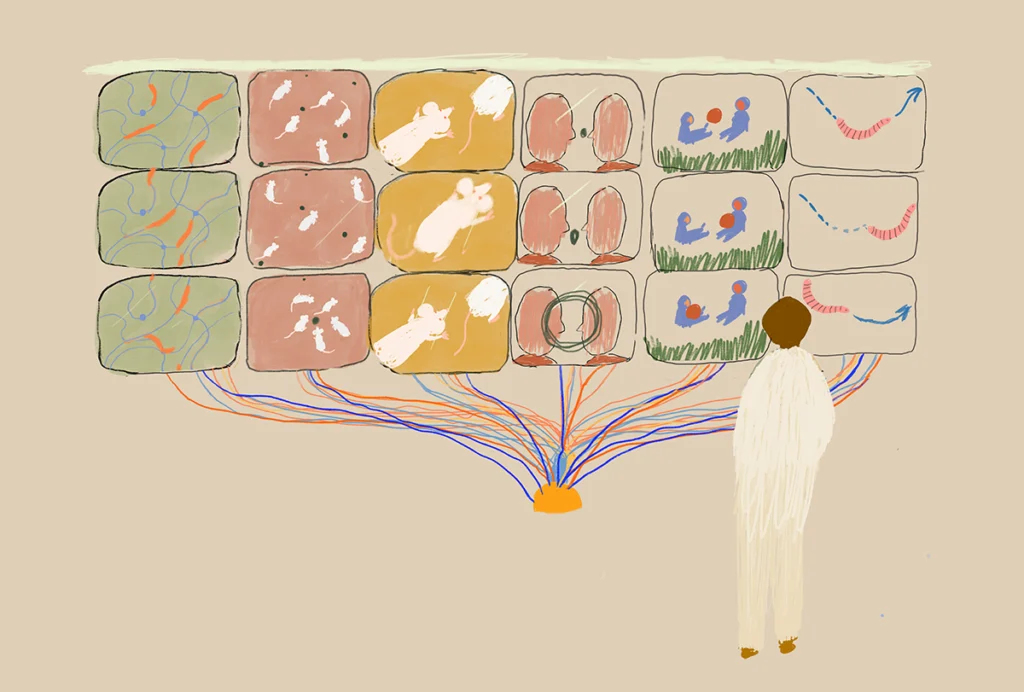

This kind of work could provide a glimpse at how mutations linked to autism alter brain signaling, says lead researcher Sergiu Pasca, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, in California.

“The larger goal here is to obtain physiological integration into the sensory system — because if you think about autism, for instance, sensory disturbance is part of the [condition],” Pasca says. “Our models need to be more realistic if they are going to capture ever more subtle aspects of human brain function.”

Making connections:

Another team reported at the same conference last year that human brain organoids can take root in mouse brains. And in work published in October, researchers transplanted individual neurons from people with Down syndrome into mouse brains1.

The new work is the first to chart the effects of a human organoid transplanted into a rat brain.

Pasca’s team infected the organoids with a form of the rabies virus that carries the gene for a fluorescent molecule. The virus can only move from human to rat cells, so only rat neurons that have made connections with cells in the organoid fluoresce.

The largest number of connections stemmed from rat cells in the cortex or in the thalamus, a region that relays sensory information. Both these regions often send signals to the sensory cortex, where the organoids reside.

The researchers then repeated the experiment with organoids induced to express a marker that fluoresces with neuronal activity. They removed the rats’ brains 160 days after transplanting the organoids.

In the brain slices, stimulating neurons that project from the rat cortex or thalamus to its sensory cortex sparks activity in the human neurons, they found.

The researchers plan to use this approach to study autism. The rat’s large brain size may enable them to insert an organoid on each side of the brain so that they can directly compare cells from an autistic individual with those from a control.

For more reports from the 2018 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

- Real R. et al. Science Epub ahead of print (2018) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

X chromosome inactivation; motor difficulties in 16p11.2 duplication and deletion; oligodendroglia

Decoding flies’ motor control with acrobat-scientist Eugenia Chiappe