Language gene mouse model could help test autism drugs

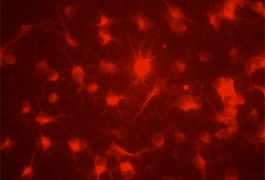

Mice lacking CNTNAP2, a gene linked to autism and language impairment, show behaviors and brain abnormalities that reflect those seen in people with disorder, according to new findings presented Thursday at the International Meeting for Autism Research in San Diego.