Left behind

High school graduation marks the end of opportunities for social engagement and access to services for many young people with autism.

From funding decisions to scientific fraud, a wide range of societal factors shape autism research.

High school graduation marks the end of opportunities for social engagement and access to services for many young people with autism.

Two new studies of families carrying glitches on a region of chromosome 16, which has been strongly associated with autism, reveal the wide range of effects caused by the variant and narrow the list of possible culprit genes.

Children with autism or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are both more motivated by money than by praise, according to a study published in January in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

The National Institutes of Health is adding a new $1 billion institute for early-stage drug development. But the agency’s plan to fund it by closing the National Center for Research Resources is causing some consternation.

A long list of autism researchers has officially rebuked le packing, a barbaric autism therapy that’s well known in France.

A new intervention that teaches toddlers skills in a real-world environment — a playgroup rather than a one-on-one interaction with a researcher, for instance — more than doubles their ability to imitate others, according to a January study in The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.

As genetic testing becomes routine, people are likely to face difficult choices about parenthood.

As autism rates rise, so do health care costs for the disorder. Despite federal programs, some children with autism are falling through the cracks in the health care system.

Accounting for gender increases the power of family-wide studies linking genetic mutations with autism, according to a study published in December in Molecular Psychiatry. The researchers use this approach to identify two candidate genes for the disorder.

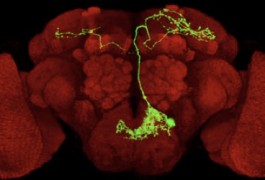

Using tricks of genetic engineering, researchers in Taiwan have created the first comprehensive map of the myriad neuronal connections in the fruit fly brain. The findings appeared 11 January in Current Biology.