Reactions from SfN 2013

Tune in for daily updates and reactions from attendees at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience meeting in San Diego, California.

From funding decisions to scientific fraud, a wide range of societal factors shape autism research.

Tune in for daily updates and reactions from attendees at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience meeting in San Diego, California.

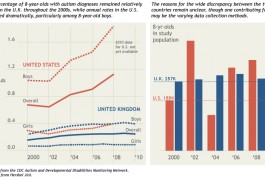

The prevalence of autism among 8-year-old children remained relatively stable from 2004 to 2010 in the U.K., reports a study published 16 October in BMJ Open. But experts say the study may be underestimating autism’s rates in the general population.

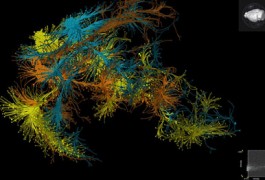

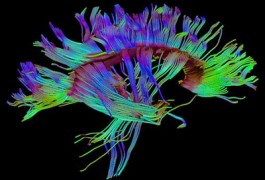

The Allen Institute for Brain Science is mapping the complex projections of neurons throughout the mouse brain. They presented results from the first 1,400 brains on Tuesday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

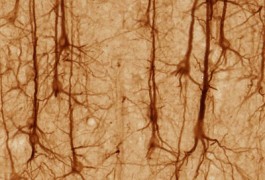

Three decades of research on anatomical changes in the brains of individuals with autism has yielded few if any consistent patterns. The field needs an overhaul of the methods used, researchers said at a symposium Wednesday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

A new tracking system allows researchers to pinpoint which of four mice is ‘talking’ as they mingle freely in a cage. The setup, presented Tuesday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, shows that male mice don’t do all the talking, as was previously thought.

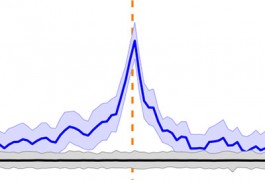

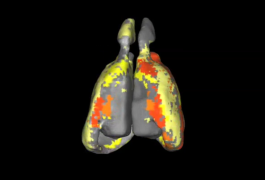

Researchers have produced images of connectivity during resting-state activation, which occurs while individuals are resting quietly in a scanner, in mouse brains. The new technique was presented Monday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Bone marrow transplants, which have been shown to arrest symptoms of Rett syndrome in young mice, have little effect on older mice, according to preliminary results presented Monday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego. The findings suggest that this approach may not be a viable treatment for those who already have symptoms of the disorder.

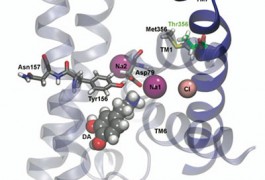

A newly discovered spontaneous mutation, described 27 August in Molecular Psychiatry, links autism to changes in the regulation of the chemical messenger dopamine.

Boys with tuberous sclerosis complex, an autism-related disorder, have more disorganized nerve fibers in some regions of the brain than do girls with the disorder, according to unpublished work presented Sunday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Geneticists react to discoveries and identify next steps for one of autism’s most promising candidate genes.