THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

The best way to understand something complex is, perhaps, to rebuild it. As a child, that’s exactly what I used to do with so many toys, from robots to trains. The rebuilt toy did not always work, but the exercise taught me how functional units, when pieced together, could work as a sophisticated machine.

As a neuroscientist, I continue to apply this lesson from my childhood to understand the human brain.

The human brain is perhaps the most complex system in the universe. It can orchestrate sophisticated behaviors and thoughts, such as language, tool use, self-awareness, symbolic thought, consciousness and cultural learning. From intricate networks in the brain emerge extraordinary technological and artistic masterpieces.

But sophistication comes at a high price. Subtle alterations in the intricate dance of early development can lead to conditions such as autism and schizophrenia.

To find clues to these alterations, my research team and I have adapted my old approach to toys: We are working to fine-tune an intricate model of the brain in a dish, built from stem cells that can mature into brain cells.

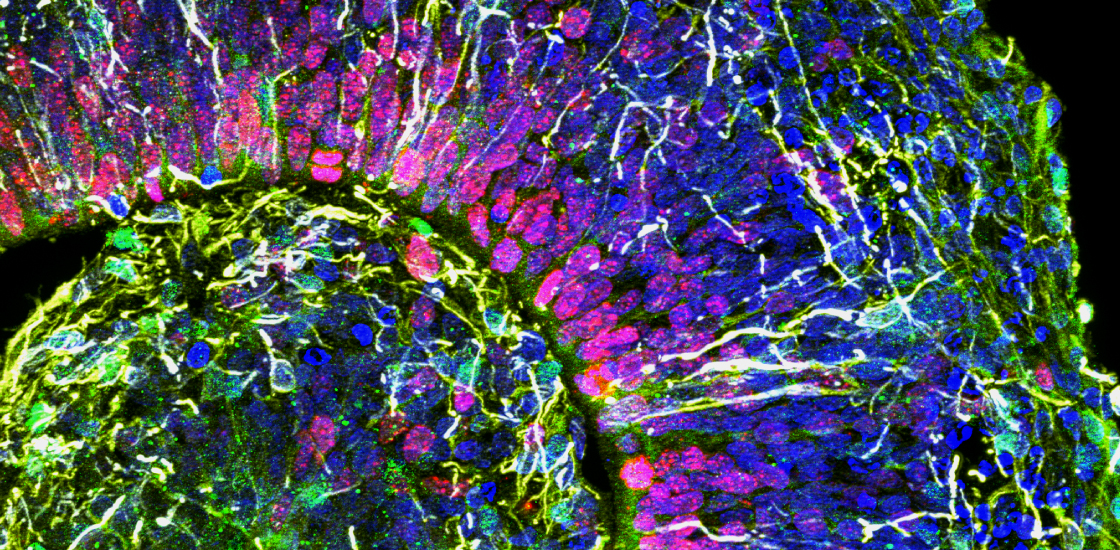

Using these so-called ‘cerebral organoids,’ or ‘mini-brains,’ we have shown that neurons derived from individuals with autism are different from those derived from neurotypical people1. We’ve also tested how environmental factors such as the Zika virus can cause microcephaly and other birth defects2. Other research groups are using mini-brains to investigate molecular and cellular mechanisms of disease, to find potential biomarkers and to test drugs.

Scientists consider mini-brains in a dish useful as semi-realistic in vitro models of human brains. As much as I believe in their potential, however, we have yet to reproduce certain critical features of the human brain in these organoids. Until we do, we cannot fully explore the possibilities of this approach.

Build-a-brain:

Past efforts to rebuild the human brain from scratch involved stem cells from early embryos. These stem cells are responsible for generating all tissues in the body. In the lab, we can expand these so-called pluripotent stem cells and give them ‘instructions,’ in the form of recipes with specific nutrients and growth factors, to become brain cells.

Scientists can also generate stem cells from living people, starting with mature blood, skin or dental pulp cells, which are easy to obtain3. The reprogrammed cells, called induced pluripotent stem cells, capture all of the donor’s genomic information.

When allowed to float freely in a solution, these cells will self-assemble into brain-like spheres that resemble the brains of human fetuses between 8 and 10 weeks gestation. Depending on the recipe, these cells can form different brain regions. My lab has focused on the prefrontal cortex, a region implicated in the asocial aspects of autism.

Yet this organoid model of the human brain has some critical limitations.

First, it is unlikely that we are growing these cells in the ideal culture conditions, because we don’t really know what is in the milieu of factors in which the human brain grows. Most of the protocols are based on rodent brain literature, and thus, several factors are likely to be missing or overrepresented.

To induce proper maturation, leading to more organized brain structures, we will likely need to optimize our culture protocols. By doing this, it is possible that we could use cerebral organoids to model even late-onset disorders, such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.

Short circuits:

Second, the brain is not only composed of neurons. Immune cells in the brain called microglia are also important in several neurological conditions. They have a different embryonic origin than neurons and are not generally in the brain organoids. Still, it is possible to generate these cells in parallel and add them to the organoids later on.

Similarly, blood vessels are also not present in these organoids, leading to an abnormal distribution of nutrients to the cells. Scientists are working on bio-printed artificial blood vessels or mixing cells that give rise to blood vessels with brain organoids, hoping they will self-organize into an intricate vascular system. Researchers also are transplanting a human organoid in an animal, so that the animal’s blood vessels naturally vascularize it4.

Lastly, and perhaps most conceptually important, we have not yet characterized these organoids at the functional level. It is unclear if the neurons in the organoid are making the right connections.

Most of the work to date is limited to mimicking gene expression patterns or anatomical organization. It is unclear if these organoids will allow us to model subtle alterations in neuronal networks and circuits that accompany conditions such as autism.

Aside from the technical bottlenecks, there is at least one obvious ethical question that comes up from the idea of thousands of human mini-brains growing inside labs. “Can the brains think?” is a question I often get from journalists.

Based on the idea that these mini-brains are not receiving or processing information, many scientists believe that thoughts arising from these brains would be unlikely. However, it is plausible that these mini-brains could process information, creating something similar to a human mind. This would open a new set of ethical concerns that would dictate how far the science can go.

Assuming such concerns can be put to rest, mini-brains could yield a multitude of discoveries and may even bring about a form of personalized medicine. In the near future, doctors may test various drugs and doses on a person’s mini-brain before writing out a prescription.

Alysson Muotri is associate professor of pediatrics and of cellular and molecular medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.