To partner with autism community, welcome dissenting opinions

Giving the autism community a voice in research means engaging in meaningful dialogue, not just making token gestures.

Spectrum’s house style is to refer to ‘people with autism’ rather than ‘autistic people.’ But we made an exception in this instance, because the author strongly prefers identity-first language.

It is rare these days to find an autism researcher who does not proclaim the value of advice from the autism community. In fact, consultations with people on the spectrum and their families are now the norm in autism research.

Community concerns

Bridging science and life on the spectrum

This new normal reflects a growing consensus that these conversations can help generate knowledge that is useful and meaningful to autistic people and their families.

There are also financial incentives to engage with the autism community: Most funders require evidence that autistic people and their families provided input on a proposed project.

Despite the widespread appreciation that these partnerships are important, there is limited understanding of how they should function. This raises the risk of tokenism, in which there is an illusion of collaboration without autistic people having any real influence on the research that affects them.

To improve the lives of autistic people and their families, researchers must interest themselves in what autistic people and their families truly need and want. Only by engaging in sincere and sometimes challenging discussions can we ensure that the field is making real progress.

Power play:

Examples of tokenism abound in everyday life. Allow me to digress briefly to illustrate this point. I am a commuter who relies on a particular train company to take me to and from London, where I work. Often, the trains are disrupted, making me late for work or getting home. This leaves me feeling, to put it politely, frustrated.

The train company is assiduous in regularly seeking my feedback on their service; company officials also make a great display of acknowledging and empathizing with the complaints I occasionally make. They assure me that my opinion is valuable in helping them improve their service — that my voice is being heard.

But in reality, I have no influence whatsoever on the company. Its officials ignore my feedback, partly because it is based on a profoundly different view of the company’s primary purpose: I believe its fundamental task is to get me to work on time and cheaply; the company is focused on generating profit for its shareholders. Also, the company is able to ignore my feedback because of the imbalance of power in our relationship: The only way I could choose to use a different train company would be if I moved to another region of England.

It is all too easy for autism researchers to slip into the position of the train company — of operating in a ‘pretend feedback’ mode, in which consultation is sought but ignored. This is a particular risk when the people giving and receiving the feedback have substantially different interests and perspectives, and when the balance of power is uneven.

For example, what does an eminent, well-funded researcher studying early intervention for autism do when told by an autistic person that she should not be trying to cure autism? And how should a funding council react when parents tell it they are not interested in genetics, but only in practical research geared toward helping their autistic children sleep better?

Agree to disagree:

Some researchers may be tempted to ignore challenging voices in the autism community — to nod and smile politely while not actually engaging. After all, it can be hard to know what to do with feedback you disagree with or do not fully understand. And it is especially difficult to assimilate ideas that you know have value, but may call for a major rethink of your work.

Occupying an echo chamber of opinions that support your preconceptions is far more comfortable than considering contradictory views.

In an influential statement on building an ethically informed approach to autism research, Liz Pellicano and Marc Stears suggest a way for researchers to avoid token dialogues with the autism community: Cherish disagreements1. They point out that within any group of stakeholders in autism research there will be different opinions — often profoundly different.

For example, even among autistic adults there are passionate disagreements about whether it is right for scientists to seek a cure for autism. Some welcome the idea, hoping such treatment would improve their lives. But others are vehemently opposed, arguing that the hunt for an autism cure is driven by a prejudiced and derogatory view of autistic people as inherently disordered.

Any conversation that seeks easy consensus will be superficial and insincere, failing to engage with important differences in perspective. Instead, what is required is respectful and open exploration of disagreement.

In my experience, welcoming disagreement is not easy. I find it uncomfortable to overtly challenge autistic people’s views on autism, as I worry that I am being disrespectful. But if we can create situations in which there is parity between researchers and members of the autism community, we can open the door to more robust and honest exchanges.

Only then can we decide what research to do and how to do it based on a real understanding of the needs and perspectives of everyone with a stake in the work. And the benefits of such an understanding are something we can surely agree on.

William Mandy is senior lecturer in clinical psychology at University College London.

- Pellicano E. and M. Stears Autism Res. 4, 271-282 (2011) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

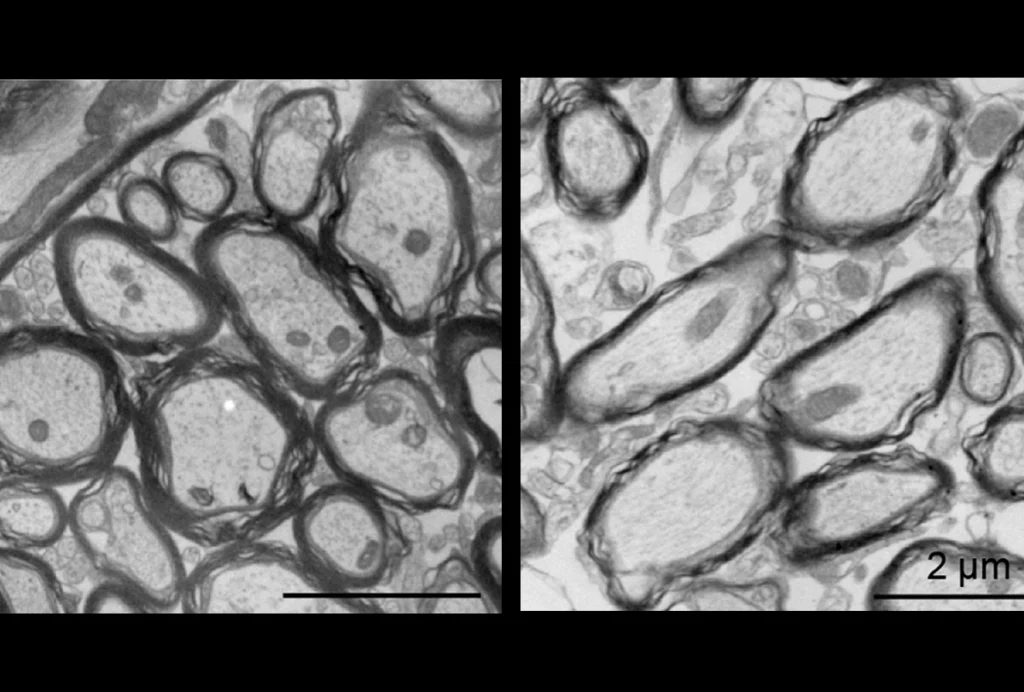

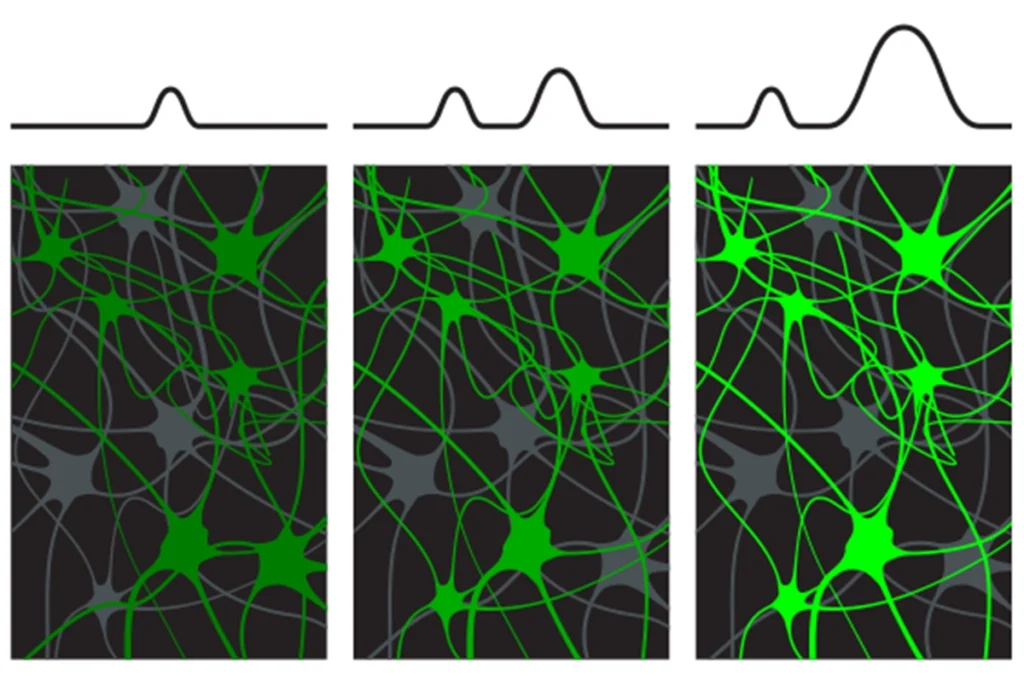

Cocaine, morphine commandeer neurons normally activated by food, water in mice