The not-so-simple synapse

In the past few days, the New York Times has run a couple of articles featuring people with autism.

Try this on for size: the human brain has about 100 billion neurons, connected by 100 trillion synapses.

We already knew that the human brain has many more neurons than the brain of any other animal, and is three times as large as even its closest relative, the chimpanzee.

In a paper in Nature Neuroscience on Sunday, scientists reported another clue to the human brainʼs superiority: synapses become increasingly more complex as you climb the evolutionary scale from single-celled yeast to humans.

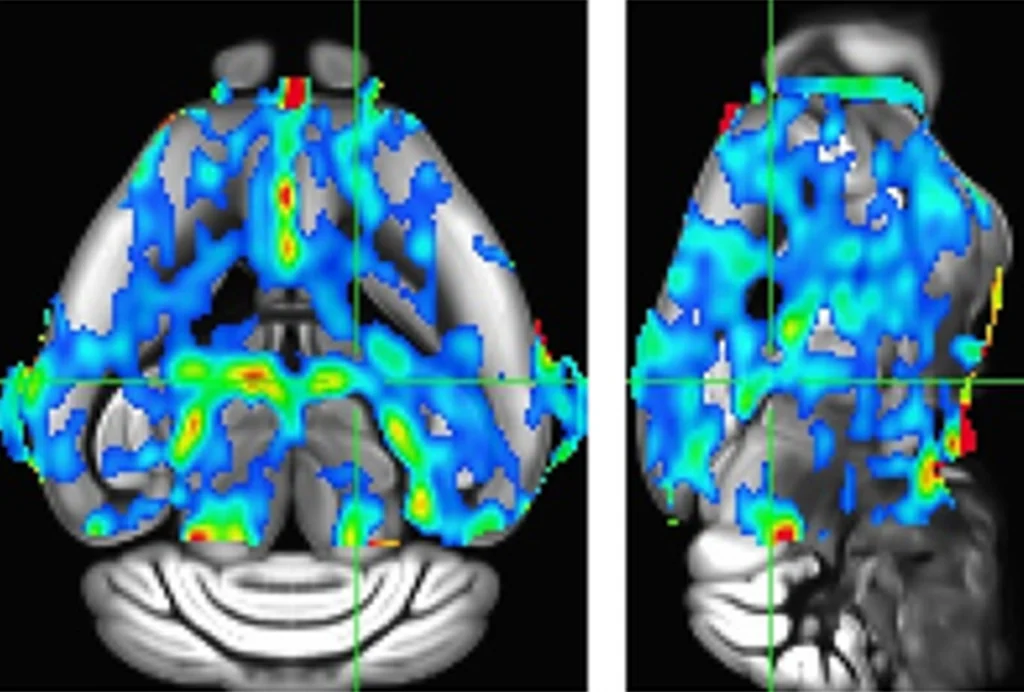

In the human brain, these 100 trillion protein-rich synapses help form specialized regions that are responsible for language, social communication, learning and memory ― all of which are affected in diseases such as autism.

There is ample evidence that synapses may be intricately involved in autism.

Mutations in neuroligins and neurexins, which together help assemble and tether synapses, are associated with the disorder; and mutations in SHANK3, a scaffolding protein, are thought to account for up to one percent of autism cases.

Explore more from The Transmitter

How inbreeding almost tanked an up-and-coming model of Alzheimer’s disease