Intelligently tested

On a non-verbal test of intelligence, people with autism perform surprisingly well — with accuracy equal to and speeds up to 40 percent faster than those of healthy controls.

090619-rspm-test-500×521.jpg

People with autism tend to score lower than average on intelligence tests. That includes the famous Wechsler intelligence scales, which assess verbal comprehension, working memory, and the manipulation of visual patterns to calculate a test taker’s intelligence quotient (IQ).

But on a less well-known test of general intelligence, people with autism perform surprisingly well — with accuracy equal to and speeds up to 40 percent faster than those of healthy controls, says a study published this week.

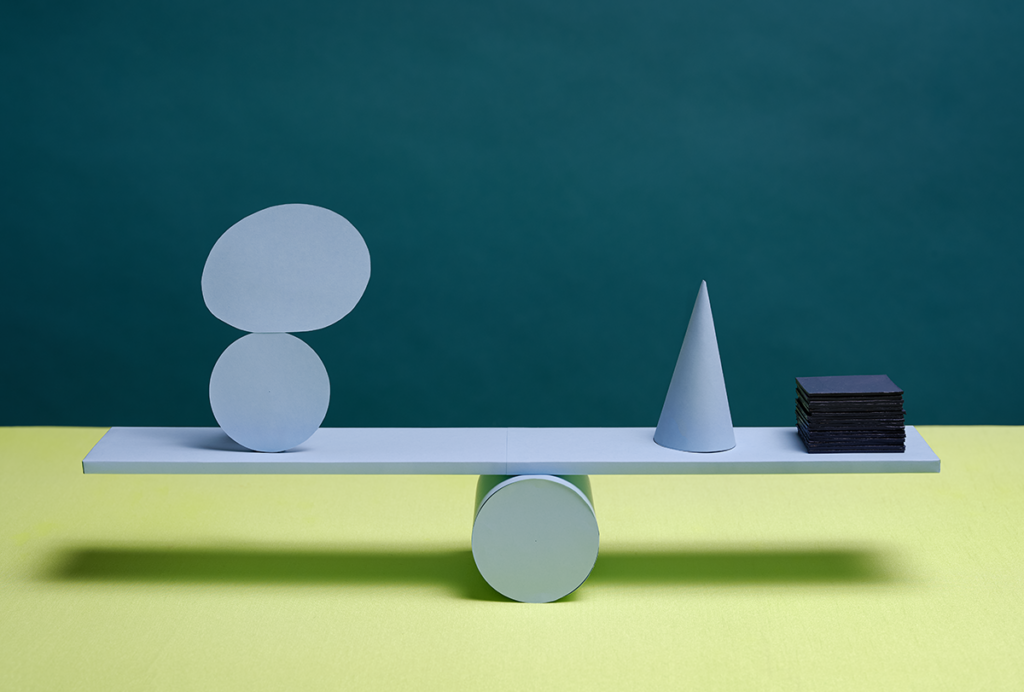

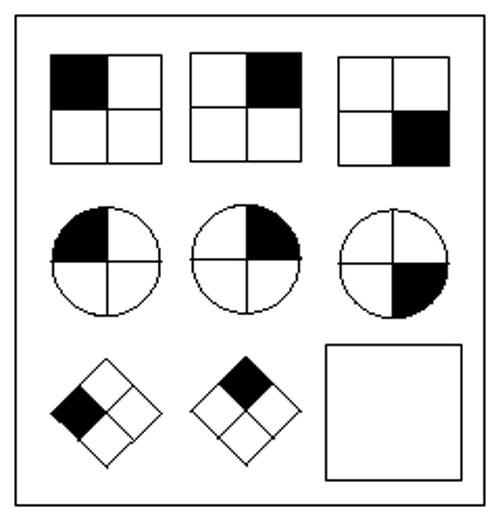

The test is called Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices (RSPM). It presents a series of figures, each showing shapes that go together in some kind of logical pattern. The task of the test taker is to figure out that pattern, and fill in a missing shape.

To ace the RSPM, you must infer rules, categorize parts of objects, and think abstractly. Unlike the Wechsler tests, you don’t need language skills, which probably explains why, in the new study, the 15 participants with autism scored just as well as the 18 controls.

But what’s behind the dramatically increased speed of the autism group? It could be that people with autism rely on different brain systems to complete the test.

To find out, the researchers had participants take the RSPM while inside a magnetic resonance imaging machine. Compared with controls, participants with autism show lower activity in brain regions typically responsible for reasoning — such as the prefrontal cortex — and higher activity in areas responsible for visual perception, toward the back of the brain.

These results add to other research showing enhanced visual processing in the brains of individuals with autism. If autism — as many have proposed — stems from weak connections between brain regions, then these studies may be yet more examples of the amazing ways in which people with autism learn to compensate for developmental deficiencies.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Inclusivity committee disbands in protest at Canadian neuroscience institute