Defining autism: A tale of two criteria?

Beyond the fuss over redrawing diagnostic boundaries for autism, the publication of the DSM-5 has sparked a more fundamental debate over whether researchers should even use it.

Last week, we released our special report on the freshly published DSM-5, the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The report includes commentary from six experts, plus an interactive roundtable, on various aspects of the DSM-5 and its impact on autism.

Check out the complete package here »

Much of the response from professionals so far is cautiously positive, even from those who were critical during the public review of the proposed revisions. Clarifications from the DSM-5 task force have calmed most worries about individuals losing diagnoses and access to services.

However, a more nuanced conversation is emerging about whether researchers and clinicians should even use the same guidelines — a talking point brought into focus by the National Institute of Mental Health director Thomas Insel’s announcement that the institute would move away from DSM categories, and echoed by others in the research community.

The buckets used to describe behavior in autism may be different from those needed to explain its causes or biology. A diagnostic category could include individuals with a disorder that has many different causes, but who require similar services. On the other hand, determining a specific biological root could lead to development of a direct therapy for that etiology.

As Insel pointed out during our DSM-5 roundtable, trying to define the genetics and underlying neurobiology of a disorder with clinical classifiers is like “trying to classify the different causes of fever by the nature of the temperature.”

In the talk, Insel suggested that, for now, clinicians ignore his proposed Research Domain Criteria — a dimensional approach focused on biological markers.

But that leaves little guidance on how researchers and clinicians might reconcile two independent frameworks for defining the disease each group is attempting to understand and treat.

What do you think?

- Generally speaking, do you think the new DSM-5 criteria will have a positive or deleterious impact on the field?

- Should there be separate guidelines for clinical providers and researchers classifying autism — one based on symptoms and the other based on biomarkers? How would the community reconcile two independent frameworks?

- The shift from Roman to Arabic numerals in the DSM-5 reportedly reflects the working group’s anticipation of incremental updates — DSM-5.1, 5.2, and so on. What do you hope to see in the DSM-5.1?

Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Or, to dig deeper, continue the conversation in the moderated SFARI Forum for researchers. Not yet a member? Learn how to register here.

Like us on Facebook » | Follow us on Twitter @SFARIcommunity » | Join our newsletter »

Explore more from The Transmitter

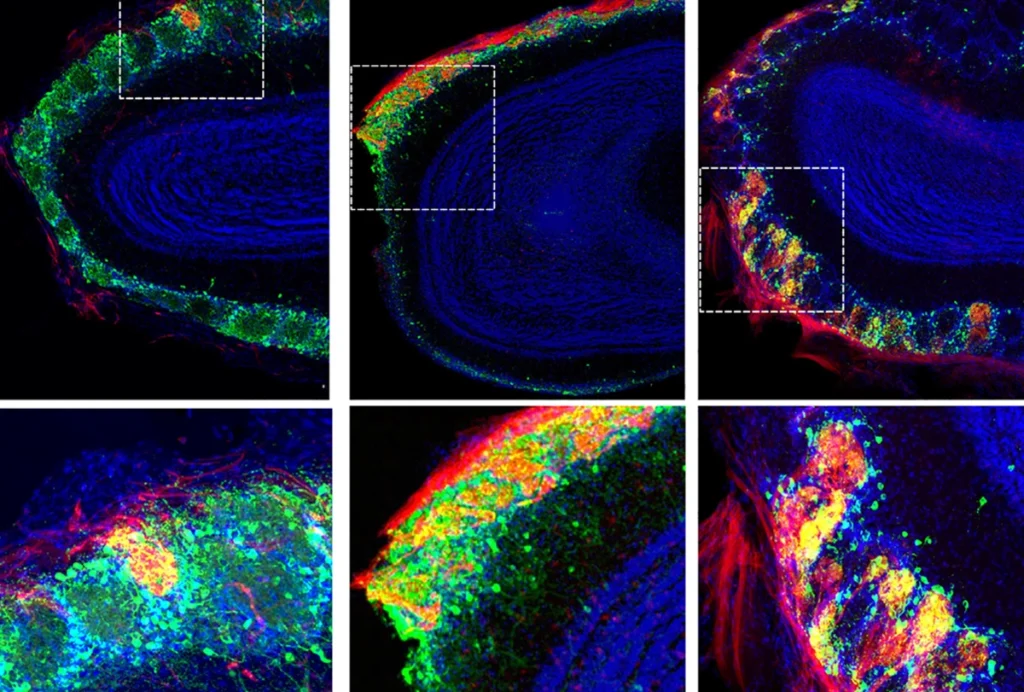

Rat neurons thrive in a mouse brain world, testing ‘nature versus nurture’