Archipelago of autism

The question of whether autism is a disease to be cured or an identity to be preserved is addressed in a review of two new books in the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

090604-archipelago-550×365.jpg

The provocative question of whether autism is a disease to be cured or an identity to be preserved is addressed in a review of two new books in the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

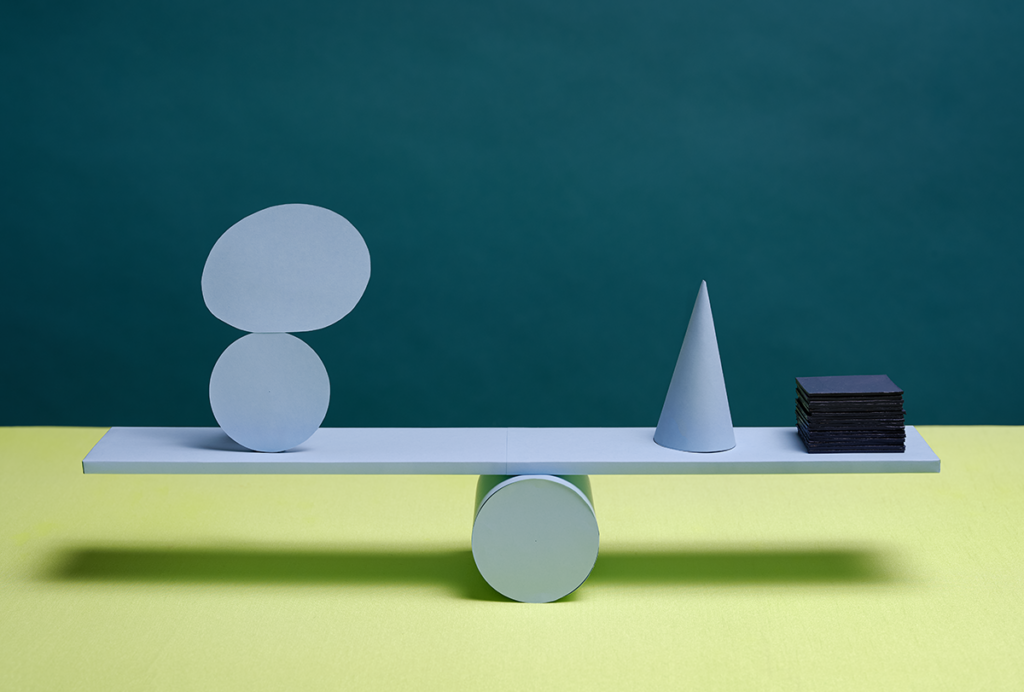

The author of the review, Jeffrey Munson, uses the vivid metaphor of an “archipelago of autism” to describe the books’ contrasting approaches.

Munson describes the first, a textbook called Autism: Current Theories and Evidence, as an atlas of the complex geographical features of these islands of autism. In 20 chapters, it presents testable scientific hypotheses of the biological roots of the disorder, such as the idea that the brain chemical serotonin may play a role, or the possibility that excess testosterone in utero could explain why more boys have autism than girls.

He calls the second book a travel guide, which provides a description of life on the archipelago for foreign visitors. In The Ethics of Autism: Among Them, but Not of Them, philosopher Deborah Barnbaum delves into more psychological and cognitive aspects of the autism spectrum, such as the theory that the condition stems from not recognizing what others desire or believe. From this perspective, autism doesn’t boil down to a disease of missing nucleotides and miswired neurons, but rather an alternate way of thinking about and interacting with the world.

It’s incredibly important for scientists (and those of us who write about their work) to consider the full diversity of the condition. For kids who constantly flap their hands, or never acquire language, autism is a disability. They could benefit from drugs that target brain circuits gone awry. But for those on the other side of the spectrum, their autistic identity doesn’t necessarily need to be ‘fixed,’ and it could teach us a lot about the mind.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Inclusivity committee disbands in protest at Canadian neuroscience institute