A shot of skepticism

Nearly 1 in every 150 children is diagnosed with autism: itʼs a statistic thatʼs often cited to ‘proveʼ that there is an autism epidemic. The reason I sound skeptical is because previous studies have found that most of the ballooning numbers can be attributed to vastly expanded diagnostic criteria for autism, and that the rise in diagnoses coincides with a drop in the prevalence of other developmental disorders.

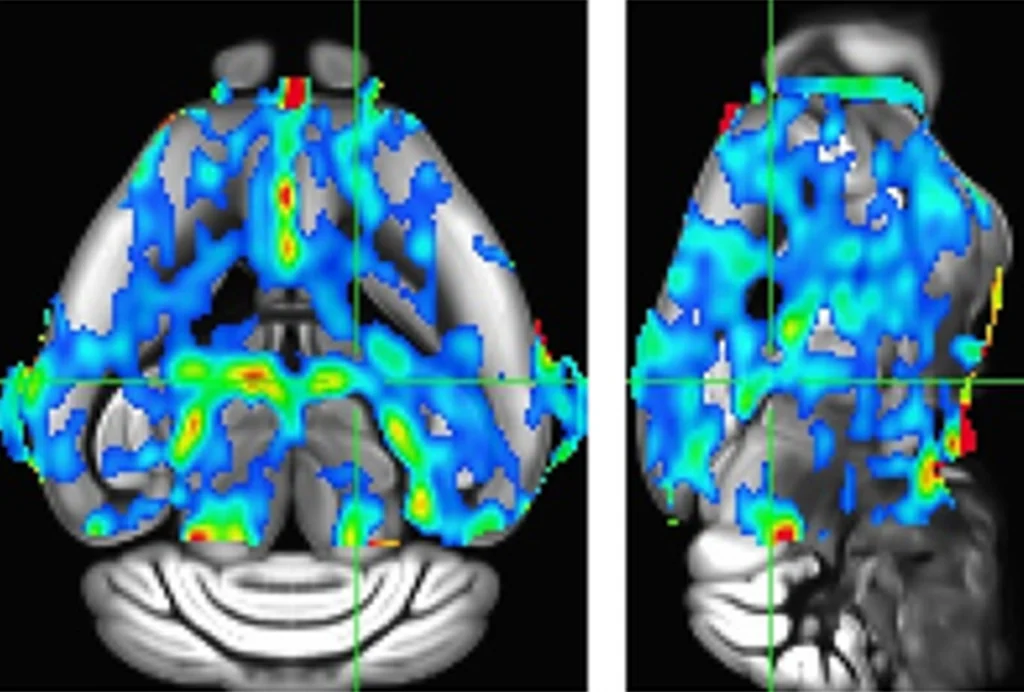

60e05359-0133-0e84-696d-632d3391d616.jpg

Nearly 1 in every 150 children is diagnosed with autism: itʼs a statistic thatʼs often cited to ‘proveʼ that there is an autism epidemic.

The reason I sound skeptical is because previous studies have found that most of the ballooning numbers can be attributed to vastly expanded diagnostic criteria for autism, and that the rise in diagnoses coincides with a drop in the prevalence of other developmental disorders.

A new study is disputing that idea. In the January issue of Epidemiology, University of California, Davis, researchers say migration patterns, greater awareness and changes in diagnostic criteria canʼt fully explain the rise in autism.

Using data from the California Department of Development Services, the researchers say autism rates in the state rose from 6.2 per 10,000 children born in 1990 to 42.5 in 2001. They also claim this is the first study to look at the effect of the age at diagnosis and the inclusion of milder cases.

Not quite, as I note above. Also, a different team reported last year that the stateʼs autism diagnoses rose from 0.6 cases per 1,000 births in 1995 to 4.1 cases per 1,000 births in 2007 ― roughly comparable numbers.

In the new report, the researchers say that changes in the age at diagnosis explains 12 percent of the increase in autism cases, and inclusion of milder cases may account for another 56 percent ― far less, they note, than the observed 700 or so percent rise.

In a statement, one of the researchers, Irva Hertz-Picciotto, said, “It’s time to start looking for the environmental culprits responsible for the remarkable increase in the rate of autism in California.” Far too much money is spent on studying the genetics of autism, she added, and “We need to even out the funding.”

Hereʼs where I should note that she and her colleagues are studying ― yes, you guessed it ― the role of precisely those “environmental culprits”, including flame retardants and pesticides. That work is unpublished, so I really canʼt judge their merit here.

One environmental factor we can safely eliminate from the list, however: vaccines. Yet another study, set to be published in the February issue of Pediatrics, has shown that there is no link between autism and the mercury-based preservative thimerosal.

In the study, Italian researchers looked at thousands of babies vaccinated for whooping cough in the 1990s with two different amounts of thimerosal. Ten years later, they found only one case of autism, and that in the group that got the lower dose of thimerosal.

Not that I expect any of this to convince the die-hard vaccine skeptics.

Explore more from The Transmitter

How inbreeding almost tanked an up-and-coming model of Alzheimer’s disease