THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

A new method allows researchers to transform stem cells into miniature intestines with a working nervous system1. The novel organs-in-a-dish could offer a platform for studying gastrointestinal problems in autism.

For years, scientists have been able to convert human skin cells into stem cells capable of becoming any type of tissue. They can then direct these cells to form tiny chunks of tissue that mimic organs, such as the brain.

In the new study, the researchers transformed skin cells into hollow blobs of intestinal tissue — complete with smooth muscle cells that contract, a type of epithelial cell that absorbs nutrients, cells that secrete mucus and neurons that fire.

The researchers first used stem cells to create immature neurons and, in a separate dish, intestinal cells, which formed spheres with distinct layers. They then combined the two cultures and mixed them in a centrifuge.

Over the next four weeks, the neural cells moved between the layers of intestinal tissue. They also matured into neurons typically found in intestinal tissue, including those that tell muscle cells to contract, the researchers reported 21 November in Nature Medicine.

Gut check:

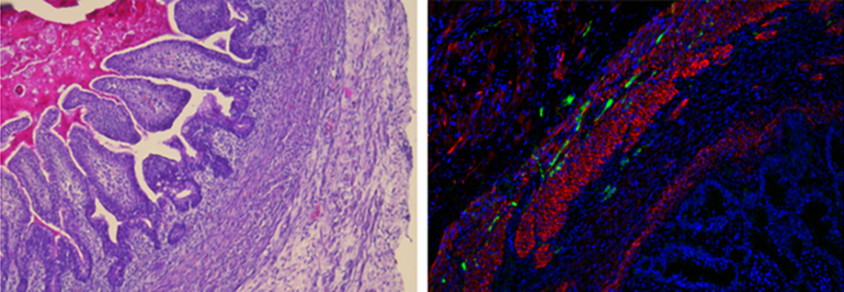

The scientists then implanted the organoids into the abdominal cavity of mice, where they grew to 1 to 3 centimeters over 6 to 10 weeks. The organoids recruit blood vessels. They develop folds and finger-like protrusions lined with absorptive and mucus-producing cells like those of the small intestine.

The tissue also contains strips of smooth muscle cells that contract in response to signals from neighboring neurons, and neurons that can sense environmental stimuli. ‘Pacemaker’ cells in the organoid set the timing for intestinal contractions.

The researchers next created organoids using skin cells that carry a mutation in a gene called PHOX2B. This gene is mutated in people with Hirschsprung’s disease, a condition marked by a lack of nerves in the colon. The immature neurons grow poorly in the resulting organoids, and markedly few develop into mature neurons.

Researchers could use a similar approach to investigate the effects of autism-linked mutations on intestinal tissue.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.