Narrower amygdala scans lead to cleaner results

Researchers have defined anatomical boundaries that minimize errors in brain-imaging measures of the amygdala, a region involved in emotion processing.

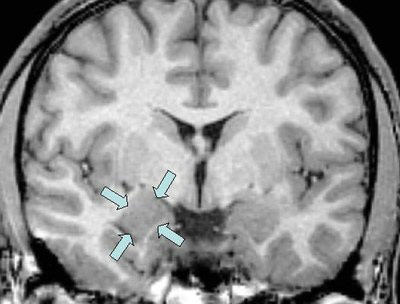

Emotional center: The amygdala, a brain region that regulates fear, is difficult to scan because of its small size and proximity to other regions.

Researchers have defined anatomical boundaries that minimize errors in brain-imaging measures of the amygdala, a region involved in emotion processing, according to a study published 5 September in NeuroImage1.

Non-invasive imaging methods such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect subtle differences in brain volume inindividuals with autism compared with controls. One form of MRI, called magnetic resonance spectroscopy, or MRS, can detect the levels of various chemicals important in brain signaling. Studies have used this technique to show differences in the activity of the amygdala between individuals with autism and controls.

The amygdala is small, however, making reliable measurements of this region problematic. For example, measurements of the amygdala sometimes overlap with those from the hippocampus, a neighboring brain structure that often has opposite patterns of activity.

In the new study, researchers scanned the amygdala of 58 volunteers in 106 individual sessions. In contrast to previous studies, the researchers defined the boundaries of the amygdala individually for each participant, rather than using a standardized area that might include parts of the hippocampus.

Using this method, the researchers scanned 30 males, 2 at each age, ranging from 10 to 24 years. The quality of the images is better with younger participants, the study found. By avoiding a region that produces low-quality data near the auditory canal of adults, the researchers were able to significantly improve the quality of subsequent scans.

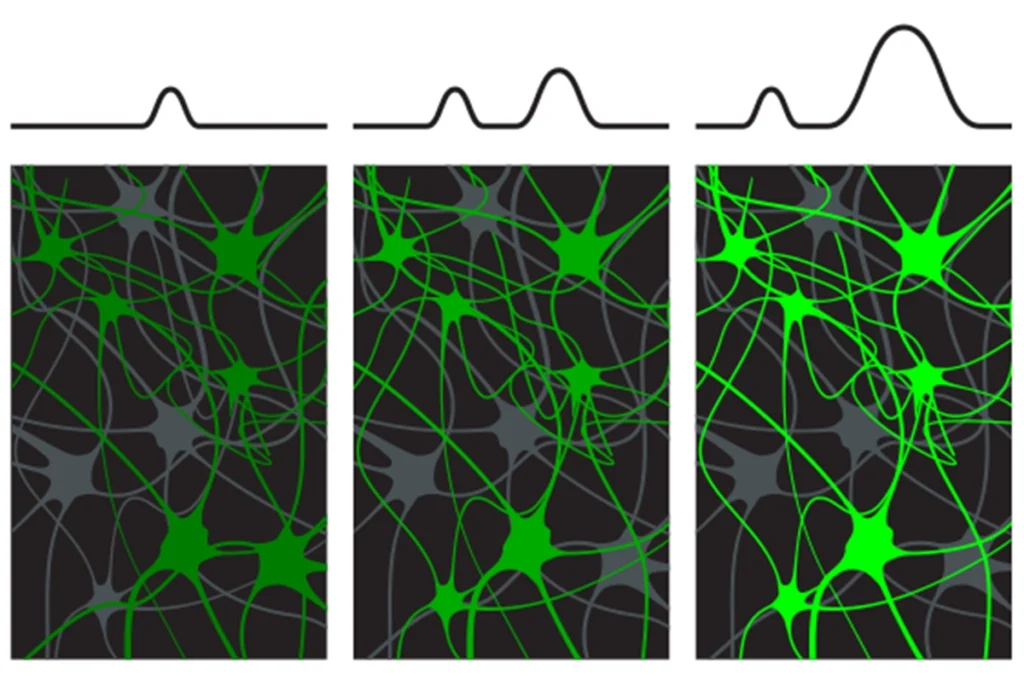

The researchers also compared four scans — morning and evening scans, two weeks apart — for each of 14 participants. In order to be statistically valid, the variability between two experimental groups needs to be smaller than between scans of the same person, something that is not always the case for amygdala studies, the researchers say.

Scans that include a wide area lead to more variable results than those that focus on a narrow region, the study found. In particular, avoiding a region near the entorhinal sulcus, a dense region easily visible on MRI scans, eliminates 29 percent of the variability for a given individual.

The researchers optimized the scan area to minimize variability and recommend using three brain regions as landmarks to constrain images of the amygdala: the optic tract, the semiannular sulcus and the entorhinal sulcus.

One caveat of the new technique is that scans of smaller areas are more vulnerable to head motion, which can also confound results, the researchers say.

References:

1: Nacewicz B.M. et al. NeuroImage Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

Cocaine, morphine commandeer neurons normally activated by food, water in mice

X chromosome inactivation; motor difficulties in 16p11.2 duplication and deletion; oligodendroglia