THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

There is no shortage of anecdotes about people with autism being highly attuned to visual detail. Temple Grandin, for instance, says that being able to detect seemingly insignificant details has helped her in her career as an animal scientist. Many parents also report that their children with autism seem unusually attentive to detail in daily life.

But a new study indicates that, at least in the laboratory, people with autism do not consistently excel at spotting visual details or struggle to see the bigger picture. The study, published 2 August in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, suggests that visual processing irregularities in autism may either be more subtle and specific than previously thought or that laboratory tests fail to capture what happens in the real world1.

Either way, these visual tendencies are “far more subtle” during laboratory tasks, says Ilse Noens, senior academic staff member at the University of Leuven in Belgium, who led the study.

Noens and her colleagues used a series of tests to probe visual processing in 59 children with autism and 58 controls between the ages of 8 and 18. The tests measure either local processing, which involves cataloging minute details, or global processing, which requires integrating disparate details into a whole.

To test local processing, the researchers asked the children to spot specific symbols, such as a red X amidst a sea of green Xs and red Cs. To test global processing, they asked the children to identify objects on a computer screen as their outlines gradually appeared, bit by bit. They also showed the children a screen filled with some dots moving randomly and some moving in a uniform direction and asked them to determine the dominant direction of the motion.

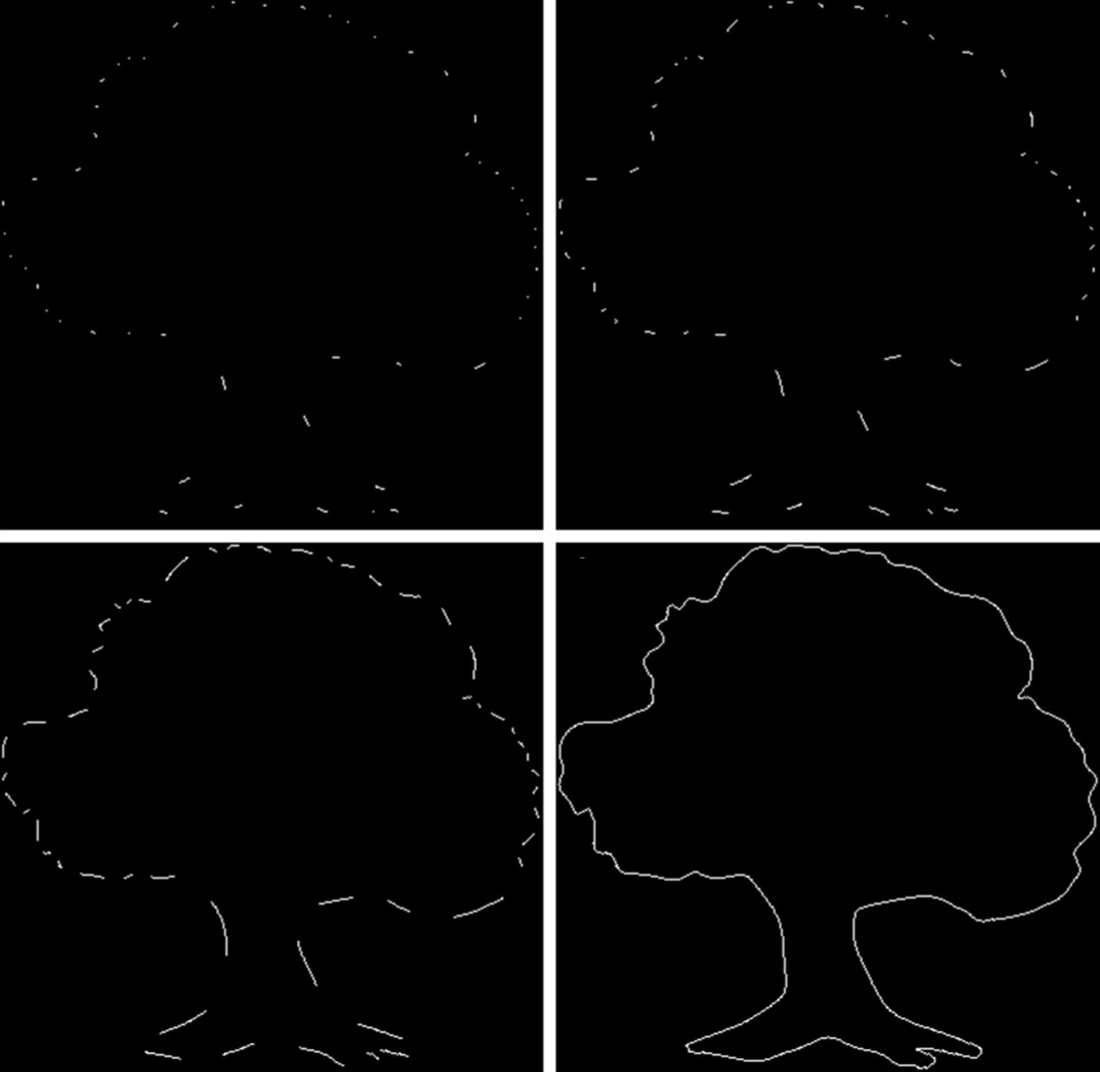

A fourth test probed whether the children naturally favor local or global processing, by having them copy a complex drawing. Researchers then scored the drawings depending on whether the child reproduced the image as an integrated whole or copied elements of it in a fragmented style.

Drawing details:

According to popular wisdom, the children with autism should have performed better on the local processing task and poorer on the global processing ones than controls. But the results were not so clear-cut.

There was no significant difference between children with autism and controls on the local processing symbol test. They found the target letters with comparable speed. Children younger than 12 with autism performed poorly on the global processing test involving moving dots, compared with similar-aged controls. But adolescents with autism were about as good as their typically developing peers at gauging the dominant direction for the dots.

When asked to identify objects by their fragmented outlines, children with autism were as quick as controls as long as the objects had distinctive features or angles. But children with autism took longer to recognize the more smooth-edged, blobby figures than controls did.

Girls with autism drew in a more disjointed style — copying pieces of figures without putting them together — than typically developing girls. Boys with and without autism showed disjointed drawing styles, too, hinting that both girls with autism and boys in general may be missing the big picture.

Previous research suggests that, in boys, the distinction in those with the disorder emerges later in life. That is, typically developing boys tend to process visual information more globally as they approach adulthood. By contrast, men with autism tend to retain a more local processing style2.

Although the researchers found some evidence that children with autism tend toward local visual processing, parents painted a starker picture of their children’s behavior. Parents of children with autism were far more likely to indicate that their children were highly detail-oriented in daily life than were parents of typically developing children, according to a survey included in the study.

“It could, of course, be that these differences become more apparent in daily life,” says Lien Van Eylen, a postdoc in Noens’s lab.

It could also be that visual processing irregularities in autism may be as diverse as the disorder itself. The next step is to investigate whether subgroups of people with autism show different visual processing styles, says Elizabeth Milne, professor of psychology at the University of Sheffield in the U.K., who was not involved in the research. “My own experience administering these types of tests to individuals with autism is there is a lot of variability,” she says.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.