© The Sanger Institute. Wellcome Images

THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Stem cells injected into young rats populate their brains with a type of neuron that dampens brain activity. The treatment makes the rats more sociable and flexible when learning tasks than they were previously.

The unpublished results were reported Saturday at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

The findings hint at the promise of stem cell therapy for autism, although any clinical application of this treatment is a long way off, says Jennifer Donegan, postdoctoral fellow in Daniel Lodge’s lab at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, who presented the findings.

In the study, Donegan and her colleagues used mouse embryonic stem cells that were on their way to becoming so-called parvalbumin neurons. This type of neuron dampens brain activity and may be lacking in some people with autism.

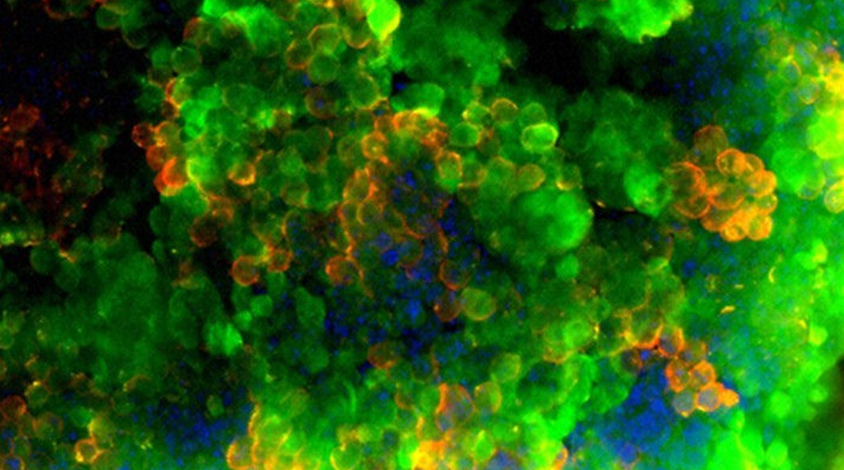

To ensure that they injected only this type of stem cell, they fused a gene for a fluorescent protein to a gene specific to parvalbumin neurons. They then used this fluorescent marker to sort the cells. This purity is important: A mixed population of stem cells could lead to brain tumors, Donegan says.

Some studies suggest that autism mouse models have fewer of these inhibitory neurons than control mice do. Other studies have shown that gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the neurotransmitter these neurons release, may be scarce in the brains of people with autism. These findings bolster the theory that some autism brains are hyperexcitable.

An influx of parvalbumin neurons might restore the balance, Donegan says.

Snack switch:

Donegan and her colleagues tried their treatment on rats born to mothers injected with an artificial virus during pregnancy, to mimic a severe infection. In people, infections during pregnancy may increase the risk of autism and schizophrenia.

These rat pups are less likely than typical pups to cry out to their mothers, an indication of social deficits. They also show signs of inflexible behavior. When researchers bury a Cheerio in a pot, the rats can learn that the pot with earth that smells like cloves (and not the one reeking of nutmeg) holds the treat. But they have trouble adapting after the researchers switch the snack to the other pot.

The researchers injected their purified stem cells into the brains of the virus-exposed rats when the animals were young adults. They then waited six weeks for the cells to take hold. The scientists also injected the rats with dead stem cells to control for the effect of any factors related to the transplant, such as an immune reaction.

The treatment increased the number of functional parvalbumin neurons in the rats. It also caused them to spend more time socializing. The rats adapted more quickly after the location switch for the Cheerio, too.

The findings suggest that boosting the number of inhibitory neurons in the brain dampens brain activity and alleviates autism-related behaviors, says Donegan. But for safety reasons, nobody is going to be treating children with these cells for some time.

For more reports from the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.