WEEK OF

October 5th

There’s some evidence that children with autism are less imaginative than their peers without the disorder. A new, more nuanced analysis suggests they struggle with specific steps in the imaginative process.

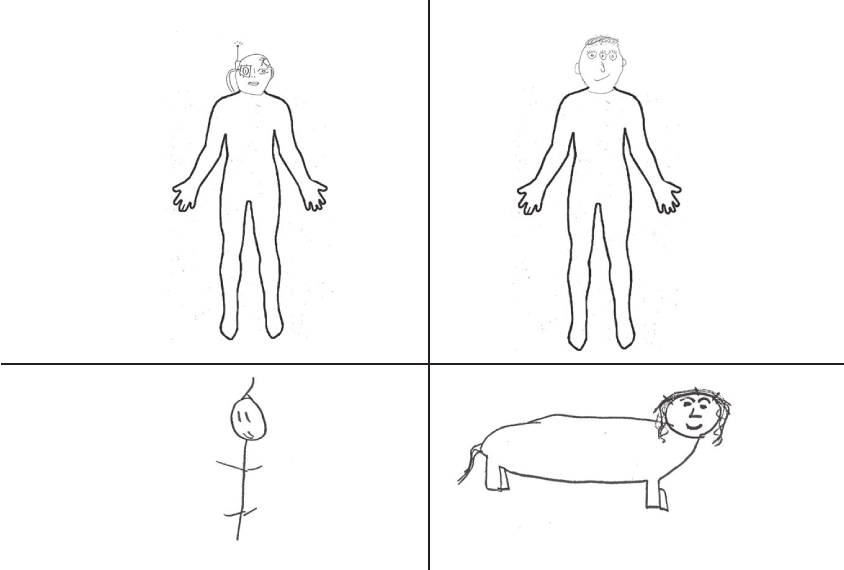

The study, published 24 September in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, uses a series of drawing tests to probe the imaginations of children with autism. In one test, a researcher asks a child to draw a person after that person has walked through a magic door that makes people ‘funny looking.’ In another task, the child has to finish a drawing of a headless person to make the person look funny. The third task involves drawing creatures that are halfway through the magic door and look half human and half something else.

Children with autism perform just as well as those with learning disabilities on the second test, in which they try to finish an image of a headless person, using specific instructions (top, left). But they struggle when asked to create ‘funny-looking’ drawings from scratch (bottom, left), hinting at difficulties in the planning part of the imaginative process. (The drawings on the right are by children who have learning disabilities but not autism.)

It’s been two months since a panel of experts tasked with weighing the pros and cons of various screening tests came out against routine screening for autism. In that time, clinicians who work with children who have the disorder and researchers who study it have been blunt in their dismay.

Most recently, Daniel Coury, chief of behavioral pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, contested the panel’s claim that there’s insufficient evidence to support screening when a child’s parents do not voice concerns. In an editorial last week in the Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, Coury argued the panel’s logic relies on the “shallow” assumption that a lack of parental concern equates to a lack of symptoms.

“Several studies have shown that many parents do not recognize signs of developmental delay,” he wrote. “Choosing not to screen because of lack of family concern is not well supported by existing research.”

Researchers have used the gene-editing tool CRISPR to modify 62 genes in a pig. The feat, detailed Monday at the National Academy of Sciences meeting on human gene editing in Washington, D.C., bests the previous record for number of genes edited in an animal by 10-fold.

“This is something I’ve been wanting to do for almost a decade,” lead researcher George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, told Nature.

Church edited the genes in pig embryos with the goal of creating porcine organs that can be transplanted into people.

While working on his book “NeuroTribes,” Steve Silberman came across four myths about autism that he says are “desperately in need of debunking.” He listed them in a story for BBC.com this week. They are:

- Autism used to be rare, but now it’s common.

- People with autism lack empathy.

- The goal should be to make children with autism indistinguishable from their peers.

- We’re over-diagnosing quirky kids with a trendy disorder.

Silberman suggests that medical experts, such as Leo Kanner and — most notoriously — Andrew Wakefield, have perpetuated many of the myths surrounding autism.

Sometimes scientists are their own worst enemies. When an experiment goes as expected, they often assume the results are right. It’s only when the results seem unusual that they double check their process.

“If nothing seems wrong, it’s easier to miss [a mistake],” Andrew Gelman, professor of statistics at Columbia University, told Nature in a story this week about how easily researchers can fool themselves. He should know, as a missed mistake forced him to retract a paper two years ago.

The story highlights a few ways that researchers can avoid deceiving themselves into thinking all is well when it isn’t. Another piece in the same issue of Nature offers tips about how best to mask your data for a more objective analysis.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.