THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Brain areas that control speech activate unusually slowly in children with autism when they move their mouths and produce sounds. The delays could contribute to language problems in people with autism, though not all the data are consistent with this idea1.

Difficulty with speaking is a common feature of autism. Several studies from the past decade suggest that split-second delays in sound processing may contribute to this problem. The new study, detailed 12 September in Autism Research, is the first to suggest that lags in speech production also play a role.

“There’s something very fundamentally different in the nervous system of an autistic child that’s kind of blocking things up and slowing things down,” says lead investigator Elizabeth Pang, a neurophysiologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

The study raises the possibility that delays along a number of different brain circuits may underlie some autism symptoms. “It’s certainly going to send all of us racing back to the lab to look at other systems to see if this is a general property of the autism brain,” says Timothy Roberts, professor of radiology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Roberts and his team first identified sound processing delays in people with autism, but he was not involved in the new work.

Still, some experts caution that the delays measured in the new study occur in children with autism who appear to have no language problems, raising questions about how the findings relate to autism symptoms.

Language lag:

A number of brain areas are active during speech production. These include motor regions that help to coordinate movements of the mouth and tongue as well as language areas involved in reading and understanding words.

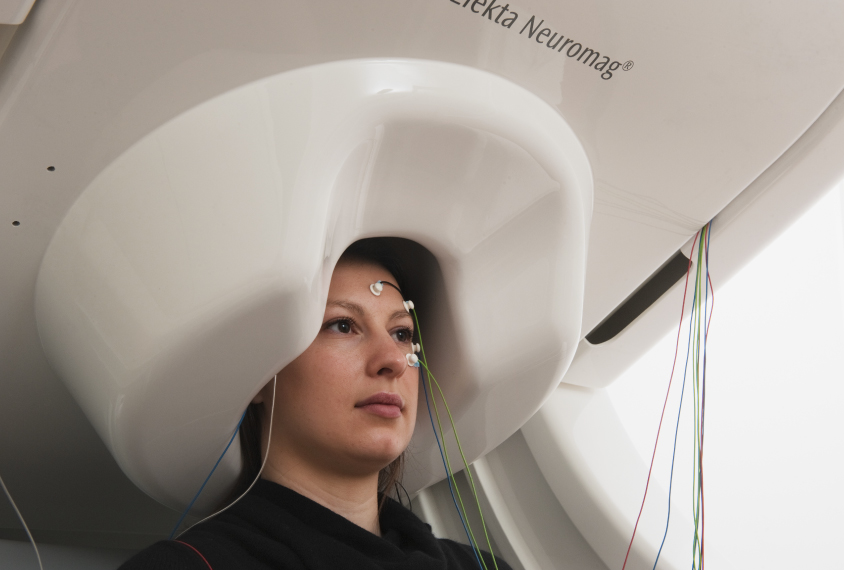

To assess whether these areas activate differently in autism, Pang and her colleagues studied 21 children with the condition and 21 controls, all between 6 and 17 years of age. The researchers used a technique called magnetoencephalography (MEG) to measure the timing of brain activation as the children performed three simple speech-related tasks.

The first task is simply opening the mouth. The second is speaking the syllable ‘pa.’ The third and most complex task requires stringing together three syllables — ‘pa,’ ‘da’ and ‘ka’ — in a single utterance, a task that involves coordinating mouth movements and breathing.

Each task builds off the one before and requires a different component of speech. “These are three different building blocks you need to have ready to go if you’re going to make a word and then make a sentence,” Pang says. “If you have problems making sentences and using language, it might be that some of these building blocks are not working properly.”

In controls, the tasks trigger the most activity in eight areas of the brain’s outer shell, called the cerebral cortex. These areas govern movement, language and the ability to integrate the two. The researchers homed in on the activity of these regions in the children with autism.

During the mouth-opening task, children with autism trail controls by about 38 milliseconds in the activation of part of the brain’s frontal cortex that governs motor planning. The delay is significant “for something that simple,” Pang says.

Delayed development:

On the single-syllable task, children with autism show a 37-millisecond delay compared with controls in the activation of a language hub in the frontal cortex. On the multi-syllable task, those with autism fall 81 milliseconds behind controls in the activation of the insula, which helps to integrate body movements with other brain functions, such as language.

“For each building block, there’s a new delay that’s introduced,” Pang says. Together, those small delays could add up to profound language problems, she says.

The findings jibe with those from a previous study showing that toddlers with autism who have the poorest motor skills tend to have the lowest speech fluency later on in childhood2. The new work adds to existing evidence that motor skills may be related to the ability to speak.

It is not yet clear whether and how the brain activity patterns seen in the study relate to language skills, however.

On average, children with autism in the study score within the normal range on tests of language use and comprehension. If their brain delays contribute to language problems, “you would then expect that the kids with autism would have worse language skills than they do,” says Helen Tager-Flusberg, director of the developmental science program at Boston University, who was not involved in the study.

The delays in brain activation may instead reflect a more generalized developmental delay seen among children with autism, Tager-Flusberg says. “It may simply be that they act more like younger children, and that might account for the differences,” she says.

What’s more, some of the findings are inconsistent and difficult to interpret. For example, although children with autism show delayed activation of the language center in the cortex while performing the single-syllable task, this region activates more rapidly in these children during the multi-syllable task compared with controls.

“The problem is that [the researchers] likely have a mishmash of kids in the autism group,” says Elysa Marco, associate professor of neurology, pediatrics and psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “That makes it very difficult to get a clean and uniform signal.”

One way to address these questions would be to look at how brain activation patterns track with language skills in individuals, rather than at differences between two groups of children, Marco says. Researchers should also look at children with autism who are genetically similar to one another, such as those who carry a deletion in the chromosomal region 16p11.2, she says.

With additional reporting by Katie Moisse.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.