Most mammals’ first social relationship is with their mother — a bond that is evident in an infant’s actions: Mice and rats, for example, gravitate toward their mother’s bedding over bedding that is clean or smells of a different dam; monkey and human infants seek out their mothers and spend more time looking at her face than a stranger’s.

Those behaviors, it turns out, rely on the signaling molecule serotonin, according to a study in mice, rats and monkeys, published today in Neuron. Animals engineered to lack the gene TPH2, which encodes a protein needed to synthesize serotonin in the brain, do not show the usual preference for their mother. And activating or silencing serotonergic neurons in mice and rats’ raphe nucleus, a brain region rich in these cells, boosts or diminishes those behaviors, respectively.

Serotonin signaling is tied to social reward in adult animals, past research suggests, and drugs that boost its transport into neurons increase sociability. The new work is the first to use a genetic approach to reveal how a molecule contributes to social behaviors in infant animals across species, the researchers assert. Yi Rao, investigator at the National Institute of Biological Sciences in Beijing, China, who led the study, and his team did not respond to requests for comment.

“It’s very rare that a paper goes from mice to monkeys and includes so much novel detail,” says Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, professor of developmental neuropsychiatry at Columbia University, who was not involved in the study. The results reveal an evolutionarily conserved circuit that drives infants to seek out time with stimuli that remind them of their mother, he says. “That’s really kind of amazing to see.”

Although some studies implicate serotonin in conditions such as depression and autism, people are not typically born lacking the ability to produce serotonin, Veenstra-VanderWeele says. For that reason, he says, the findings may not have direct relevance to humans.

Still, the results can help researchers understand how the molecule shapes brain development and early social bonds, and how that could influence social behavior later in life, says Robert Froemke, professor in New York University’s Neuroscience Institute and otolaryngology department, who was not involved in the study.

R

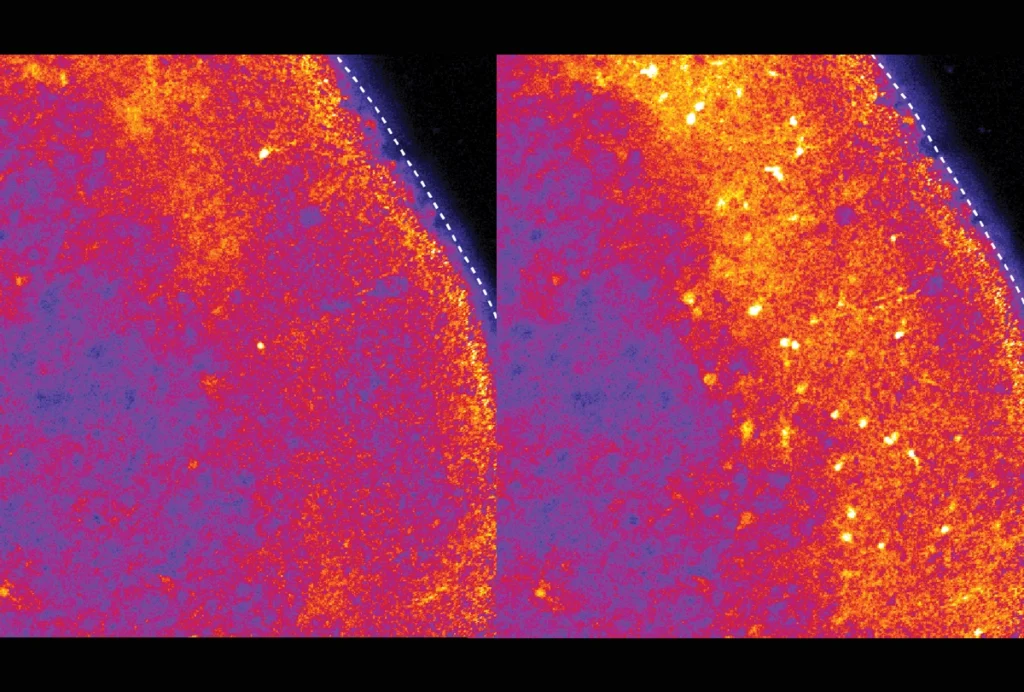

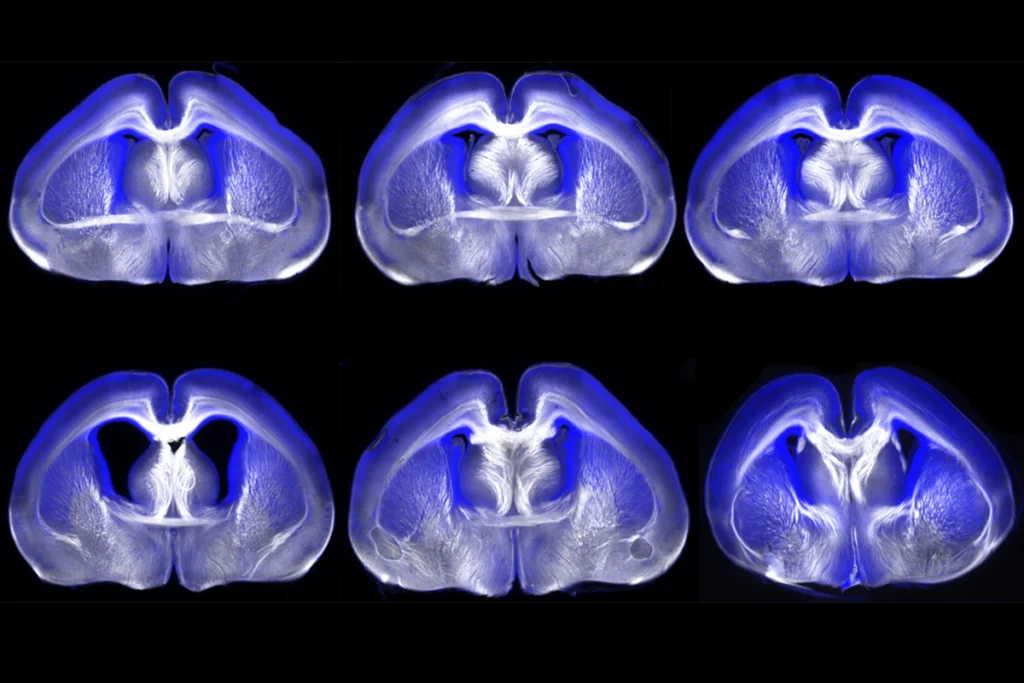

ao and his colleagues did not set out to study how infants bond with their mothers, they write in their paper. More than 10 years ago, they were studying adult mice that lack the TPH2 gene and noticed that, as infants, these animals had unusual behaviors.In the new work, the team found that the knockout mice — as well as TPH2 knockout rats — did not show the typical preference for their mother’s bedding. Rhesus macaque monkeys engineered to lack TPH2 also spent less time clinging to or interacting with their mother when she was awake or sedated. And the knockout monkeys showed no preference for an image of their mother’s face over images of other monkey moms.

Pharmacologically lowering serotonin levels in heterozygous rat pups and monkey infants caused the animals to lose their behavioral preferences for their mother, the team found. Boosting serotonin levels in the knockout animals, on the other hand, induced a preference.

When wildtype mice sniff their mother’s bedding, they show a burst of activity in serotonergic neurons in the raphe nucleus, calcium imaging revealed. And oxytocin-signaling neurons in the paraventricular nucleus are also activated by the maternal odor, further analyses showed.

What’s more, activating a serotonergic circuit — neurons that project from the dorsal raphe nucleus to the paraventricular nucleus — induced maternal preference behaviors in mice that previously lacked them, an optogenetics experiment demonstrated.

S

imilar to the serotonin knockout animals, rats lacking the gene for oxytocin showed no preference between bedding from their mother and that from a different dam, Rao and his colleagues found. And treating either of these animals with intranasal oxytocin induced a maternal preference.But whereas pharmacologically increasing serotonin levels could rescue that behavior in animals lacking TPH2, the same did not work for oxytocin knockouts. That result suggests that oxytocin acts downstream of serotonin, the researchers say: Administering oxytocin provides a way to work around the serotonin deficit.

The serotonin-oxytocin relationship they describe differs slightly from what has been reported in the past. A 2013 study of social reward in adult animals, for example, found serotonin to signal downstream of oxytocin. But that may be because the two studies examined different brain areas, says Robert Malenka, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California, who led the 2013 work.

“The common high-level conclusion is that serotonin and oxytocin interact in complex ways to influence a variety of social behaviors,” he says.

The work raises a number of questions that future research can dig into, Froemke says. “How is the serotonin system actually set up? How is it responding to maternal odor?” And for tiny animals that cannot yet explore the world on their own, “What good is that?” he adds. “It’s fascinating stuff.”