THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Triggering immune defenses in pregnant mice leads to autism-like behaviors not only in their pups, but also in the following generations, suggests a new study1.

Having a severe infection during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of having a child with autism, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. In pregnant mice and monkeys, immune responses to pathogens can alter brain development and lead to behaviors in the pups like those seen in all three brain conditions.

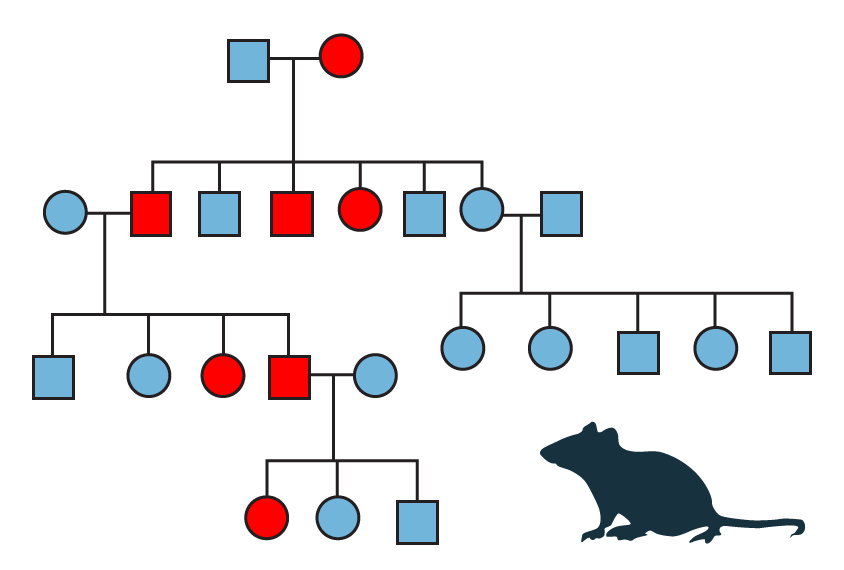

The new study found that some of these traits, including social and sensory problems, are present even in the following two generations — specifically among the pups whose fathers were exposed to a viral compound in the womb. The findings appeared 29 March in Molecular Psychiatry.

How these traits are passed down through generations is not known, though researchers are exploring a role for chemical modifications to sperm DNA that could arise from the prenatal exposures. “It’s worth putting more effort into finding out what the mechanisms are and how we can prevent those effects,” says lead investigator Ulrike Weber-Stadlbauer, assistant professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

The study hints that signs of autism might be present in some grandchildren of women who had severe infections during pregnancy, says Alan Brown, professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University, who was not involved in the study. “It could be that we should be studying two generations ahead and not just one when looking at preventable risk factors,” he says.

Bridging generations:

Weber-Stadlbauer and her team injected pregnant mice with poly(I:C) — a compound found in some viruses — to mimic a viral infection and stimulate the mother’s immune system. When the pups were 10 weeks old, the team assessed their social, sound-processing, and learning and memory abilities.

Both male and female pups show social impairments: Unlike typical mice, the pups do not choose to interact with an unfamiliar mouse over an object.

They also respond differently from controls in a learning and memory task. They can learn to associate a sound with a painful shock, but they spend more time than controls do frozen in fear when the tone isn’t followed by a shock, hinting at alterations in emotional learning.

The mice may have hearing problems as well. A typical mouse shows a diminished startle response — in which it contracts its body’s large muscles — to a loud sound if it has just heard a quieter one. The exposed animals, however, show the full response to the loud noise even after hearing a softer sound, indicating that they process sounds differently than controls do.

When the researchers mated prenatally exposed male and female mice with controls, they found that the pups from the males also show social and cognitive impairments, but do not have sensory problems. The pups of the males also show a symptom not seen in their parents: When forced to swim for extended periods, trapped in a glass cylinder, they spend more time than controls do floating motionless — a behavioral sign of despair.

The researchers found the same atypical behaviors in one more generation of mice descended from exposed males. By contrast, the first generation of mice descended from the exposed female mice behave normally. (The researchers did not test subsequent generations descended from females.)

The findings suggest that the abnormal behaviors in these rodents are somehow passed through males, and can persist for at least three generations.

“We think that it might be transmitted by the male germline — so, by the sperm,” says Weber-Stadlbauer. “But we haven’t shown any proof of how it’s transmitted, so we can only speculate.”

Tags in sperm:

The researchers also found that prenatal exposure to the viral chemical alters patterns of gene expression in the amygdala, a brain region involved in social behavior, fear and depression.

They identified 2,217 genes for which expression levels are unusually high or low in the prenatally exposed male and female mice, 4,015 that are altered in the pups of these mice, and 1,132 genes whose expression is altered in both groups. Some of these genes function during brain development and a few, including RELN, NRXN3 and FOXP2, are linked to autism.

The behaviors and gene expression patterns in the animals prenatally exposed to the viral chemical are not necessarily identical to those of later generations. “It seems that this transgenerational transmission is not a simple mirror of the effects that you see in the first generation,” Weber-Stadlbauer says. “There’s also a modification over generations.”

Her team is examining the patterns of chemical markings on the DNA of sperm from exposed males. Exposure to other types of environmental factors, such as diet and stress, may influence these ‘epigenetic’ tags, which may alter gene expression patterns.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.