THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Editor’s Note

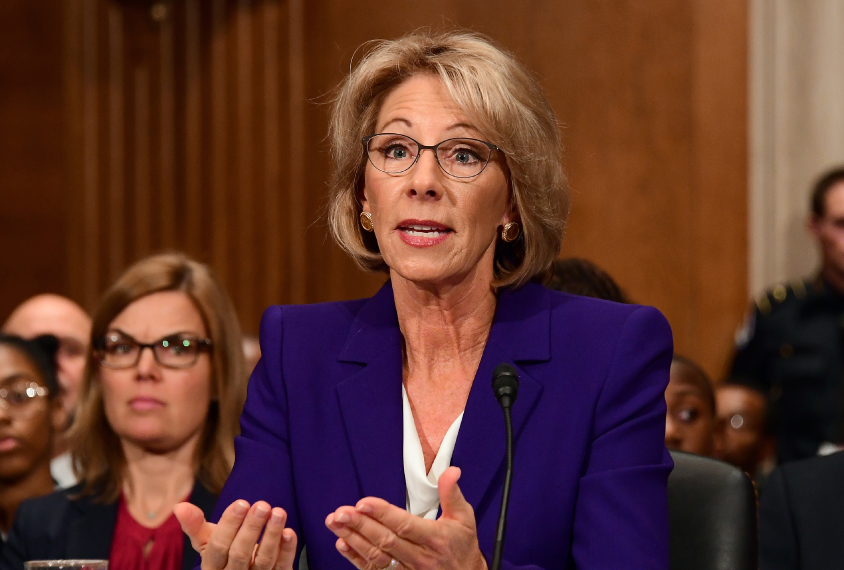

The U.S. Senate today confirmed Betsy DeVos as secretary of education, after Vice President Mike Pence cast a historic tie-breaking vote. This updates the article below, which was originally published 1 February 2017.

Autism researchers and advocates alike are sounding the alarm as President Donald Trump’s pick for U.S. secretary of education — billionaire Betsy DeVos — heads to the Senate floor for confirmation. DeVos, they say, is unqualified and unfamiliar with the policies that most affect the rights and education of children with autism.

Yesterday morning, the Senate education committee voted 12-11 along party lines to advance DeVos’ nomination to a vote by the full Senate. The date for that vote has not yet been set, but it could happen as early as this week.

“We are in deep, deep trouble as an autism community in the next four years,” says Matthew Siegel, faculty scientist at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute. “It’s going to be a wild ride.”

Siegel and others point to DeVos’ advocacy for private and charter schools which, unlike public schools, have no federal obligation to provide services for children with autism or other conditions. And in mid-January, she stumbled on questions from the Senate education committee about the law that grants children with disabilities the right to education in a public school.

“I think she’s a terrible choice for all children in public schools, and children with autism especially,” says David Mandell, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania. “She’s made it clear that she wants to divert money away from traditional public schools — the schools in which 85 percent of American children, and a higher percent of children with disabilities, receive their education.”

DeVos has also come under scrutiny because she and her husband are major investors in Neurocore, a Michigan-based company that offers a controversial treatment for people with autism.

“We have a lot of evidence-based treatments that actually do help children with autism,” says Fred Volkmar, director of the Yale Child Study Center. Her awareness of autism treatments is limited to one that “has not yet been shown to be effective,” he says.

Pivot points:

DeVos has a troubling track record on schools and education policy. In Michigan, she advocated to divert state funds away from public to private and charter schools, and fought against oversight of how that money is spent.

During the first round of questions by senators two weeks ago, DeVos said that individual states should decide whether their schools must comply with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). But IDEA is a federal law. It requires schools receiving federal funds to provide special education services to children who need them.

“She either didn’t know it’s a federal law, and that any state that takes federal money for education is obligated to abide by IDEA — or she does know that IDEA is a federal law and she’s saying that we’re not going to enforce it,” Mandell says. Either scenario, he says, is problematic.

DeVos pivoted a week later, however, stating in a letter to a Georgia senator that she will uphold the special education law.

Any loss of federal funds for public schools — whether through diversion of money to private and charter schools or through lapses in the enforcement of IDEA — is likely to affect children with autism in inner cities the most, Mandell says.

That’s because schools in these areas depend primarily on federal funds for their services. By contrast, schools in wealthy, suburban districts benefit from hefty property taxes.

DeVos’ policies could also exacerbate racial and ethnic disparities in public education for children with autism, says Connie Kasari, professor of human development and psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Kasari says she has unpublished data showing that in the Los Angeles public school district, white children with autism receive more services than do Hispanic children with the condition. “Private education is not going to solve this problem,” she says.

Private education can be counterproductive for children with autism, adds Samantha Crane, legal director and director of public policy for the Autistic Self Advocacy Network. Private schools tend to focus on coercive behavioral management rather than on academics, and isolate children with autism from their typical peers, she says. “[The children with autism] can end up with worse behaviors.”

Funding fracas:

DeVos’ financial stake in Neurocore, valued at up to $25 million, has also sparked concerns. The company promotes the use of a technique called neurofeedback to treat behavioral challenges in people with autism.

In the controversial technique, a child dons a cap of electrodes that allows him to see his brain waves on a computer. The child plays a game or performs other tasks, and is rewarded with, say, extra points when he shows brain activity patterns resembling those seen in a neurotypical child.

There is limited evidence to support this sort of treatment in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, says Sven Bölte, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, who studies neurofeedback. “But in autism,” Bolte says, “we don’t even have any good hypotheses about how to use it the best way.”

Neurocore representatives did not respond to a request for comment.

DeVos’ stake in the company shows a lack of judgment, and raises concerns that taxpayer money could be funneled to the for-profit company, critics say.

“This is a woman who believes there’s nothing wrong with promoting this [treatment] and profiting from it,” says Lily Eskelsen García, president of the National Education Association, a Washington, D.C.-based labor union that represents teachers and other public school staff.

García says she could envision a scenario in which schools might use federal funds to pay for questionable treatments such as the Neurocore approach rather than proven behavioral therapies. “This should alarm anybody — whether you have children or not — who cares about mental health,” she says.

The date for DeVos’ confirmation vote is unclear, but García says it could happen soon. Whenever it happens, DeVos is likely to be approved, because there are 52 Republican senators and only 50 votes are needed to confirm her nomination. However, two Republicans have said they are not sure whether they will vote for her.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.