Male prairie voles are more sensitive to early-life parenting than female voles are, according to a new study. The male pups are especially sensitive to the level of care provided by their fathers, the work also shows.

The results “rigorously established that there are sex differences in the effects of early social experience,” says Devanand Manoli, assistant professor of psychiatry at University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

Prairie voles are a particularly useful model for studying the effects of parenting behaviors because, unlike many other animals, they are typically raised by two parents rather than just one, says lead investigator Jessica Connelly, professor of psychology at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

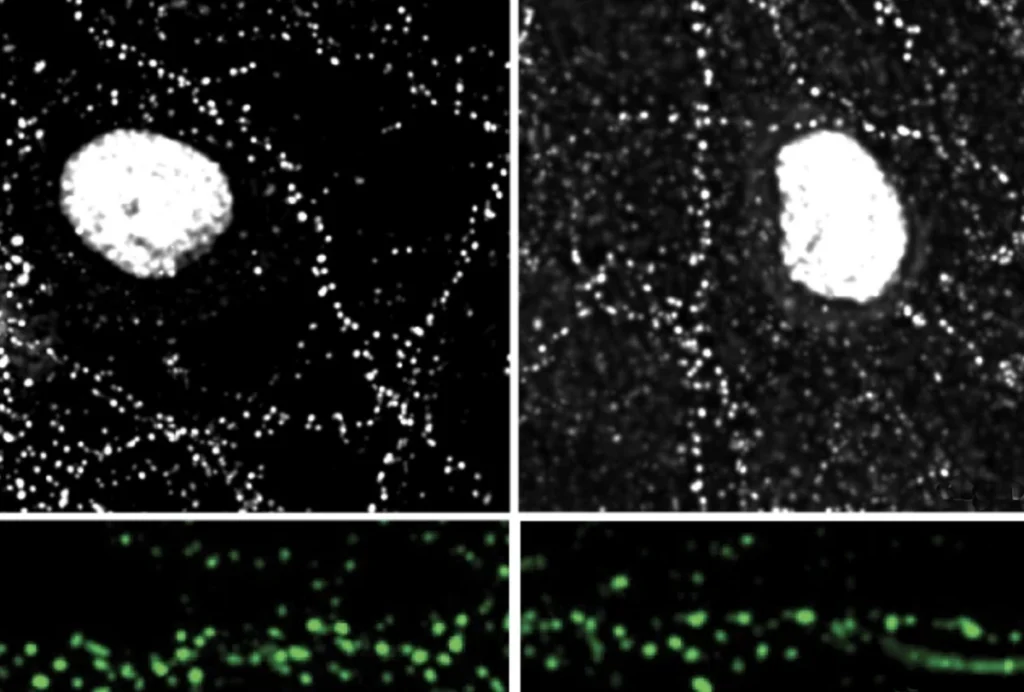

She and her team quantified prairie vole parents’ levels of attentiveness to their pups before weaning the pups from their mothers two to three weeks later, at which point the researchers evaluated several aspects of the pups’ brain development, including gene expression, synaptic density and epigenetic markers of age.

Animals raised by the least attentive parents showed more epigenetic changes associated with increased aging — as measured by DNA methylation in the nucleus accumbens — than those raised by more attentive parents, suggesting their brains had developed faster.

And the male, but not the female, pups raised in a higher-care environment had different expression levels of 321 genes in the brain, 42 of which are linked to autism. Of those 321 genes, 175 showed higher expression, and 146 showed lower expression, compared with those in male pups raised in lower-care environments. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in July.

“By understanding what happens in typical neurodevelopment, I hope that we can begin to uncover why regulation of these genes differs in males and females,” says Joshua Danoff, a postdoctoral associate at Rutgers University who worked on the new study while a member of Connelly’s lab. “This ultimately will allow us to understand why mutations in these genes lead to much stronger autism traits in males and why females require a higher mutational burden to display autism phenotypes.”

T

And “even though a lot of these genes were affected, that doesn’t mean the animals are autistic,” adds Robert Froemke, professor of genetics and neuroscience at New York University in New York City. The dysregulated genes impact a variety of functions in the brain, including neuroplasticity.

Lastly, the team found the fathers’ care in particular shaped the neural development of their male pups. Those with greater care from fathers than from mothers — which show less variation in how much time they spend caring for their pups — had smaller synaptic terminals and a higher density of asymmetric synapses in the nucleus accumbens, an area of the brain associated with motivation, reward and risk-taking. Male pups of attentive vole fathers were also more likely to display parenting behavior toward pups that weren’t theirs, a common behavior in typical adolescent voles.

Froemke and Manoli both say the nucleus accumbens was a logical place to start searching for molecular changes but that they look forward to future studies that might reveal the involvement of other circuits or brain regions that communicate with the nucleus accumbens.