THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Just as search engines comb through the vast expanse of the Internet for information, several online resources are helping scientists browse massive collections of data on the brain. Researchers showcased several of these increasingly popular resources Saturday afternoon at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Results of most neuroscience studies conducted in the past few decades are available online, and much of the raw data has been funneled into online repositories, such as the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the National Database for Autism Research.

Still, “data can be really hard to find,” says Jeffrey Grethe, associate director of the Center for Research in Biological Systems at the University of California, San Diego. That’s because some 2,000 biomedical databases are part of the so-called ‘hidden Web,’ meaning they do not link together or expose themselves to search engines.

In 2005, the National Institutes of Health began developing a website, the Neuroscience Information Framework (NIF), to collect and smartly curate troves of data. Now led by Grethe and his colleague Maryann Martone, NIF contains searchable information from about 200 databases related to neuroscience, and is visited by about 45,000 people a month, Grethe says.

“What we do is tie directly into data sources to make them searchable and useable by the research community,” Grethe says. “It’s a one-stop shop.”

For example, NIF contains a catalog of commercial antibodies made by some 200 vendors. It also includes brain connectivity data from sources such as the Allen Institute for Brain Science, clinical trial information from clinicaltrials.gov, and descriptions of animal models of autism from SFARI Gene, a database of genes and mouse models relevant to autism. (SFARI Gene is funded by the Simons Foundation, SFARI.org’s parent organization.)

Brain wiki:

One of the largest projects under NIF’s umbrella is NeuroLex, which aims to be a Wikipedia for the neuroscience community.

“There’s pages and pages of information about things in neuroscience and anybody can edit them,” says Stephen Larson, chief executive officer of MetaCell, an informatics start-up based in San Diego. Larson created NeuroLex in 2009 when he was a graduate student in Martone’s lab.

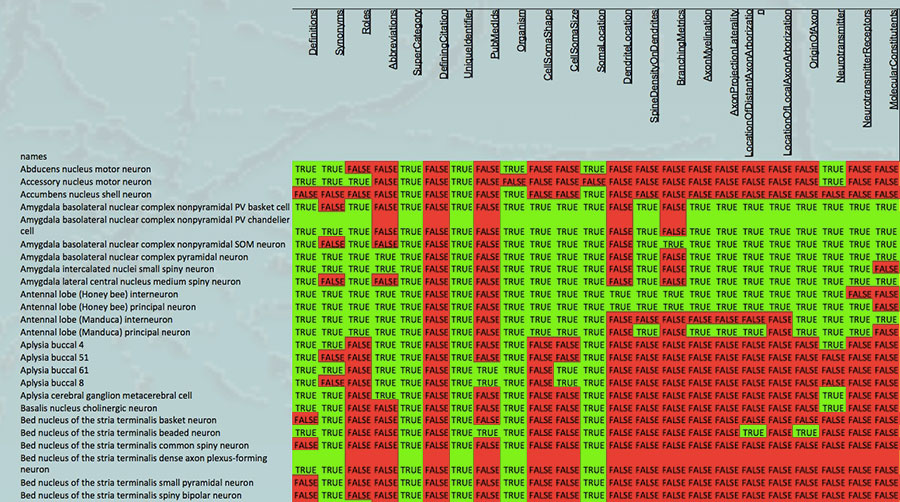

For example, NeuroLex has crowd-sourced information about more than 700 different types of neurons. For each type, a user can look up dozens of details, such as the species it is found in, the neurotransmitters it produces and the brain regions to which it projects.

The site also has information about behavioral paradigms, brain regions, neurotransmitters, brain diseases and even funding resources. A search for ‘autism,’ for example, brings up pages on the Autism Chromosome Rearrangement Database and the Autism Tissue Program.

NeuroLex receives about 500 hits a day, Larson says, and 80 percent of its traffic comes from Google searches.

As with Wikipedia, the information in NeuroLex’s pages is sometimes in dispute. In fact, that’s part of the goal, Larson says.

“We wanted a place on the Web where those kinds of conversations can happen,” he says. “You can see edits on pages that happen with intervals of 6, 9 and 12 months, where somebody comes to it and then later revises it.”

Other resources gaining popularity include sites that allow researchers to deposit new, exquisitely detailed information. For example, in the Brain Architecture Management System, or BAMS2, neuroanatomists can document precise connections — and the strength of those connections — between brain cells in animal models.

“Mapping connectivity data is a huge bottleneck,” says Mihail Bota, research associate professor at the University of Southern California, who created the resource a few years ago. “Everybody wants to know the circuitry of the brain, but that involves many tens of thousands of connections.”

BAMS2 is meant to help researchers sift through published circuit data from any of several species — for example, amygdala connections in the rat. In addition to the search function, BAMS2 allows researchers to add connections they’ve discovered. This can be done privately or as part of the searchable resource.

The software also allows researchers to visualize circuits at many levels, from a connection between two cells to networks that span regions.

All three of these new projects are bellwethers of neuroscience’s heavy reliance on informatics.

“There are huge quantities of data which can be handled only by computers,” Bota says. “Without tools like these, we can’t do any of it.”

For more reports from the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.