THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Lowering the levels of OTX2, a protein found in the fluid that bathes the brain, prevents many abnormal behaviors in mouse models of Rett syndrome. The unpublished results, presented today at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, highlight a potential treatment strategy for people with the syndrome.

“Nobody would think to look at this molecule normally, because it’s not expressed anywhere in the postnatal brain [cells],” says lead investigator Takao Hensch, professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, who presented the findings.

OTX2 is primarily expressed in the choroid plexus, the cells lining the fluid-filled spaces, or ventricles, in the brain. The choroid plexus produces cerebrospinal fluid, the nutrient-rich solution that envelops the brain and spinal cord.

OTX2 is known to support the structure and function of a group of neurons that express a protein called parvalbumin and dampen brain signaling. Blocking OTX2 lowers parvalbumin expression and impairs the neurons’ activity.

In 2012, Hensch’s team reported that mice missing the Rett gene MeCP2 have an excess of parvalbumin cells and inhibitory signaling in the visual cortex when they are 15 days old. This age is about 15 days before the mice begin to show Rett-like features, including low body weight, movement and breathing problems and premature death.

In the new study, Hensch and his colleagues investigated whether OTX2 plays a role in the inhibitory signaling.

Neuron regulator:

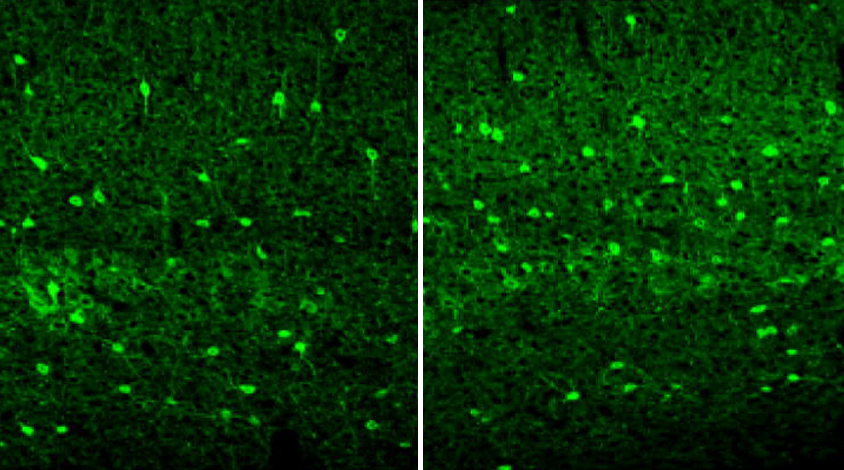

At 15 days of age, the Rett mice show an increase in parvalbumin neurons throughout the brain, the researchers found. The finding suggests that this phenomenon extends beyond the visual system the team focused on in the 2012 study.

Compared with controls, the Rett mice have more OTX2 in the choroid plexus and in the visual cortex. The protein binds to ‘perineuronal nets,’ web-like structures that surround the parvalbumin neurons.

The researchers injected mice with a molecule that interferes with this binding. This treatment lowers parvalbumin levels — although it is unclear exactly how — and normalizes the firing patterns of the neurons.

Deleting a copy of OTX2 in the Rett mice prevents the mice from developing Rett-like features, the researchers found.

For example, the double-mutant mice weigh more than Rett mice do and perform better on a test of motor coordination. They also live about twice as long as those missing only MeCP2. The researchers saw similar results when they used a virus to lower OTX2 levels in the choroid plexus.

“When you see these mice in the cage, you can’t tell the difference from [controls],” Hensch says. “They’re running around, they have a shiny coat, they’re healthy looking.”

The double mutants also have normal levels of parvalbumin in the cortex and typical cortical thickness. “It’s exciting that knocking down OTX2 far away from the cortex actually can rescue both of these phenotypes,” Hensch says.

Not all of the Rett-like features disappear, however. The double mutants still show low muscle strength and irregular breathing.

As a step toward translating their findings into people, Hensch and his colleagues examined postmortem brain tissue from four women with Rett syndrome and four controls. They saw increased levels of parvalbumin in the Rett brains. Hensch says his team also has seen elevated OTX2 levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of girls with the syndrome.

Because substances in the bloodstream can pass more easily into the choroid plexus than they can into the brain, Hensch says he is optimistic that his team will be able to develop a treatment that can regulate OTX2 expression in people with Rett syndrome.

For more reports from the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.