Neuroscience journal retracts 13 papers at once

The papers were flagged by a method that has now been called into question.

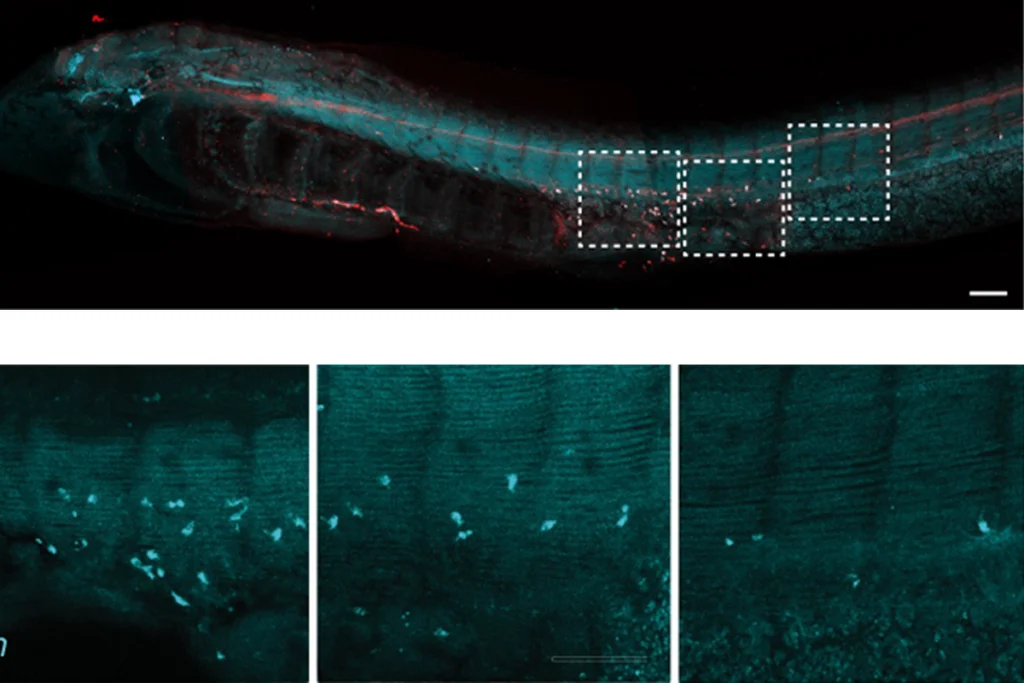

A neuroscience journal has retracted 13 articles in one go after noting that each included “material that appeared fraudulent.”

All of the papers appeared in Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, a journal published by IOS Press, between 2018 and 2021. Bernhard Sabel, the journal’s editor-in-chief and professor of medical psychology at the University of Magdeburg Medical School in Germany, told Spectrum that he first flagged the papers in late 2021.

Before issuing the retraction, Sabel checked each paper for “multiple” signs of problems and asked each author to respond to a questionnaire. He says it took him more than a year to investigate all of the papers by hand.

“Some authors were either unresponsive, unable to provide a reasonable explanation for having done so, or they volunteered to withdraw their paper without specifying the reasons why,” the 2 May retraction notice states.

But some of Sabel’s criteria for flagging the papers — that they come from scientists affiliated with Chinese hospitals, and that the corresponding authors used private, non-academic email addresses — have come under criticism.

T

One of the retracted papers, entitled “Astragaloside IV regulates the HIF/VEGF/Notch signaling pathway through miRNA-210 to promote angiogenesis after ischemic stroke,” was published in 2020 and has 30 citations; at least 19 of those citing papers were authored by physicians at Chinese hospitals and list private email addresses.

None of the corresponding authors of the retracted papers responded to Spectrum’s requests for comment. But Sabel says that some have started responding to him.

“Now that the authors received the retraction notice, they write me emails stating that they did not look at their mailbox and missed our reminders that [they] had a retraction warning,” Sabel wrote in an email to Spectrum. “For years???? Yeah ;-).” Sabel suggests that the retracted articles may have come from a paper mill, an organization that sells fraudulent research papers.

I

“Doctors in China are too busy to do the research, yet they are under extreme publication pressure to keep their job or advance,” Sabel says. “Purchasing a paper is a way out.”

In February 2020, China’s Ministry of Science and Technology discouraged institutions from paying researchers for publishing in high-impact journals such as Nature or Cell, and encouraged them to move away from paper-based metrics for career advancement. The now-retracted papers were published from 2018 to 2021.

I

Based on these criteria, Sabel estimates that some 380,000 “fake publications” are published each year. “The number of publications in my journal has dropped to almost half since I became more aware and trained myself to pick out the fake papers,” he says.

But Sabel also notes the high false-positive rate: 44 percent. And other researchers have been quick to criticize the preprint, which has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

“I think it’s a real overstatement. It’s just wildly too overconfident to say if these things are present, there’s surely something terrible going on,” says Heathers. “380,000 papers is so much higher than any other estimate that exists.” A 2016 paper from data sleuth Elisabeth Bik found that about 2 percent of biomedical papers (out of a sample of more than 20,000) had signs of intentional image manipulation.

Guillaume Cabanac, associate professor of computer science at the University of Toulouse in France, agrees with Heathers and points to a Mastodon post by Carl Bergstrom, professor of biology at the University of Washington: “They flag 44 percent of the known real papers as fake,” Bergstrom wrote. “That’s not a detector, it’s a coin flip.”

Sabel acknowledged that “in the ideal world the false-alarm rate should be zero, but in the real world this is unrealistic.” Additional indicators would make him more certain that a given paper is actually fake, he wrote in an email to Spectrum.

“But our goal was not to develop a detection tool which tells the editor ‘this is a sure fake’ but to provide a tell-tale that the respective paper should be explored further (additional scrutiny),” Sabel continued, calling his results “rough estimates” that were “shockingly high.”

“If you even accept half of our estimates, it is still a huge problem in need to be eliminated (if possible),” he wrote. He said the 90 percent sensitivity of his method makes him confident that it is useful.

Cabanac previously created the Problematic Paper Screener to scrape text from papers and flag those that use “tortured phrases,” weird strings of words meant to get a paper past plagiarism detectors. His tools have flagged more than 20,000 papers to date. One such paper about autism was retracted last month following reporting by Spectrum.

Other, more sophisticated paper-mill detectors are also in the works. One of them, developed by STM (also known as the International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers) screens papers “for more than 70 signals that could indicate that the manuscript has been generated by a paper mill,” according to reporting in Nature. The tool has been trialed by Elsevier, Taylor & Francis, and Frontiers journals, but its algorithm and results have not been publicly revealed.

Still, detectors are unlikely to ever solve the problem completely. “Hospitals have put these poor people in an impossible situation,” Heathers says. “You have to feel a bit sorry for them. But at the same time, the papers need to go.”

Explore more from The Transmitter

$278 million cut in BRAIN Initiative funding leaves neuroscientists in limbo

Reporting bias widespread in early-childhood autism intervention trials