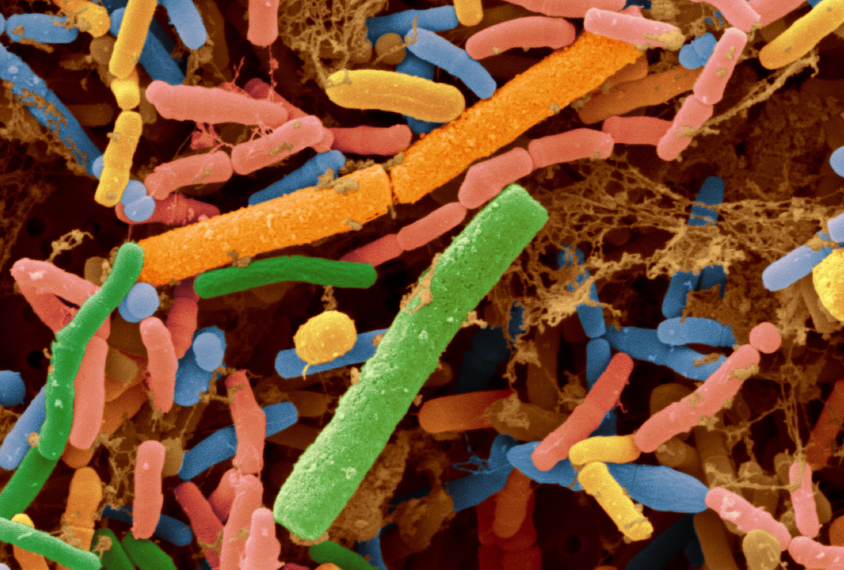

Scimat / Science Source

THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Replacing the microbes that inhabit the gut eases digestive troubles and social difficulties in children with autism, suggests a pilot study1.

About half of children with autism have gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea and constipation. Some children with autism have fewer types of gut microbes than their typical peers2. And an oral dose of the microbe Bacteroides fragilis improves gut function and eases autism-like repetitive behavior in mice.

The new study tested the idea that transplanting microbes may ease some autism features. The study included just 18 children and lacked a control group of untreated children with autism. Still, the findings hint that the regimen is safe and effective for children with autism.

“Modifying the gut microbiota shows a lot of promise as a future therapy,” says lead investigator Rosa Krajmalnik-Brown, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Arizona State University.

The treatment is not a home remedy: The researchers screened fecal matter for harmful pathogens before extracting microbes for the transplant.

“This excellent work advances the emerging concept that gut bacteria impact behavioral and gastrointestinal outcomes” in people with autism, says Sarkis Mazmanian, professor of biology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, who was not involved in the study.

Transplant test:

The participants, aged 7 to 16 years, all have autism and gut problems. They took an antibiotic once a day for 14 days to wipe out their gut microbes. They then fasted for 12 to 24 hours while taking a laxative to flush out their intestines.

The researchers then transplanted a large dose of gut microbes from people screened for infections, gut problems and neurological conditions.

Half the children drank the microbes in a beverage such as juice or chocolate milk three times a day for two days. The other half received the treatment once through the rectum. All of the children drank low daily doses of the microbes for another seven to eight weeks. They also took a drug that suppresses stomach acid to help the microbes survive their trip through the stomach and into the intestines. The treatment lasted 10 weeks.

The researchers evaluated the children’s gut problems and autism features before, during and after the treatment, and again eight weeks later. They also periodically collected stool samples from the children and compared the mix of microbes to that of 20 untreated typical children.

The treatment decreased the occurrence and severity of abdominal pain, indigestion, diarrhea and constipation by 82 percent on average. Of the 18 children, 16 improved, and remained better eight weeks after treatment.

The treatment also improved children’s scores by 22 percent on a test used to diagnose autism and assess its severity. The children’s social skills improved on a different test. These improvements lasted at least until the end of the study.

The transplant increased microbial diversity in the children’s stool. The microbial gut populations of the 16 children who improved looked similar to those of controls at the end of treatment and for two months afterward.

However, with so many components to the therapy, it’s impossible to know whether the microbe transplant itself — as opposed to, say, the antibiotic — is sparking the improvements, says Mark Corkins, professor of pediatrics at the University of Tennessee in Memphis, who was not involved in the study.

Krajmalnik-Brown and her colleagues are planning a multisite trial in which participants would be randomly assigned to receive a treatment or a placebo. Such a trial would allow the researchers to control for some of the variables they encountered in the pilot study.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.