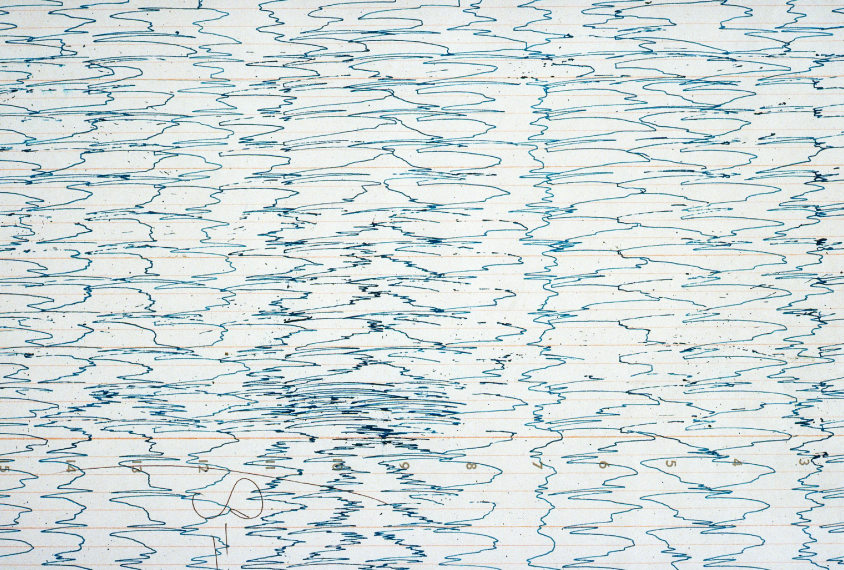

Southern Illinois University / Science Source

THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Introducing the gene UBE3A into neurons that dampen brain activity can prevent seizures in a mouse model of Angelman syndrome. But it only works when the gene is added at a young age.

Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Angelman syndrome is marked by developmental delay, epilepsy and, often, autism. It usually stems from a deletion of a stretch of DNA on chromosome 15, where UBE3A resides. Some people with Angelman lack only UBE3A or carry a mutation in the gene.

Last year, Benjamin Philpot and his colleagues showed that mice missing UBE3A in a subset of neurons that quiet brain activity, called inhibitory neurons, are unusually susceptible to seizures caused by a drug or a loud noise. Deleting the gene from neurons that ramp up brain activity, called excitatory neurons, has no effect on seizures.

In the new work, the researchers showed that introducing UBE3A in inhibitory neurons when the mice are young — the equivalent of childhood or adolescence — can prevent the mice’s increased susceptibility to seizures. Introducing the gene when the mice are adults has no effect.

“If you intervene early, you can prevent subsequent epileptogenesis,” says Philpot, professor of neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “There’s a very well-defined critical period.”

Inhibitory effect:

Philpot and his team studied mice missing UBE3A only from inhibitory neurons, which communicate with the chemical messenger GABA. The mice express UBE3A in their excitatory neurons, which use glutamate to communicate. (The balance between inhibitory and excitatory brain signaling is altered in epilepsy and thought to be altered in some people with autism.)

The researchers used a drug to induce seizures in adult mice. They did this daily for eight days. This increases the animals’ susceptibility to drug-induced seizures months later. Children with Angelman syndrome also show an increased susceptibility to seizures over time.

“Seizures beget seizures,” Philpot says.

The mice were engineered such that the researchers could restore UBE3A in inhibitory neurons using a chemical. They did this in juvenile mice, in adult mice that had not yet experienced a seizure, and in adult mice that were already having seizures.

Restoring the gene in juvenile mice prevents the increased susceptibility to seizures later on; restoring it in either set of adults has no effect.

“This is informing us when in development we need UBE3A and in which cell types,” Philpot says. “If we can narrow down the relevant cell types and the time at which they’re disrupted, we’ll be in a better position to develop therapeutics.”

Philpot plans to reinstate UBE3A in a subset of inhibitory neurons to identify specific circuits that underlie seizures in Angelman syndrome.

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.