FDA approval of trofinetide may spur further drug development for Rett

The drug, welcomed by patients, might be just the first of many.

There had never been a medication approved specifically to treat Rett syndrome, so when Deanna Adair heard about a clinical trial of a drug called trofinetide that could potentially help her daughter’s symptoms, she signed up.

Adair knew trofinetide had been studied before, so she wasn’t afraid to enroll Zoey, then 6 years old. Zoey had already been through more than five years of acid reflux, constipation, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic ear infections and asthma, in addition to the typical Rett syndrome characteristics of verbal communication loss, gait issues and hand-wringing. “We kind of figured, well, let’s see what it might do for Zoey,” Adair says. The phase 3 trial started in 2019, and her daughter enrolled in it at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania shortly after.

The drug was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last week, making it the first-ever treatment for Rett syndrome, a rare genetic neurodevelopmental condition that shares some traits with autism. Trofinetide, a synthetic analog of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) peptide, now branded as Daybue, was developed by Australia’s Neuren Pharmaceuticals before being licensed in North America to Acadia Pharmaceuticals in 2018.

Yet Daybue might be just the first in a raft of treatments for Rett syndrome. Kathie Bishop, Acadia’s senior vice president and head of rare disease and external innovation, agrees that the approval will likely accelerate drug development for the condition. Daybue’s approval, she says, will show others what’s possible.

A

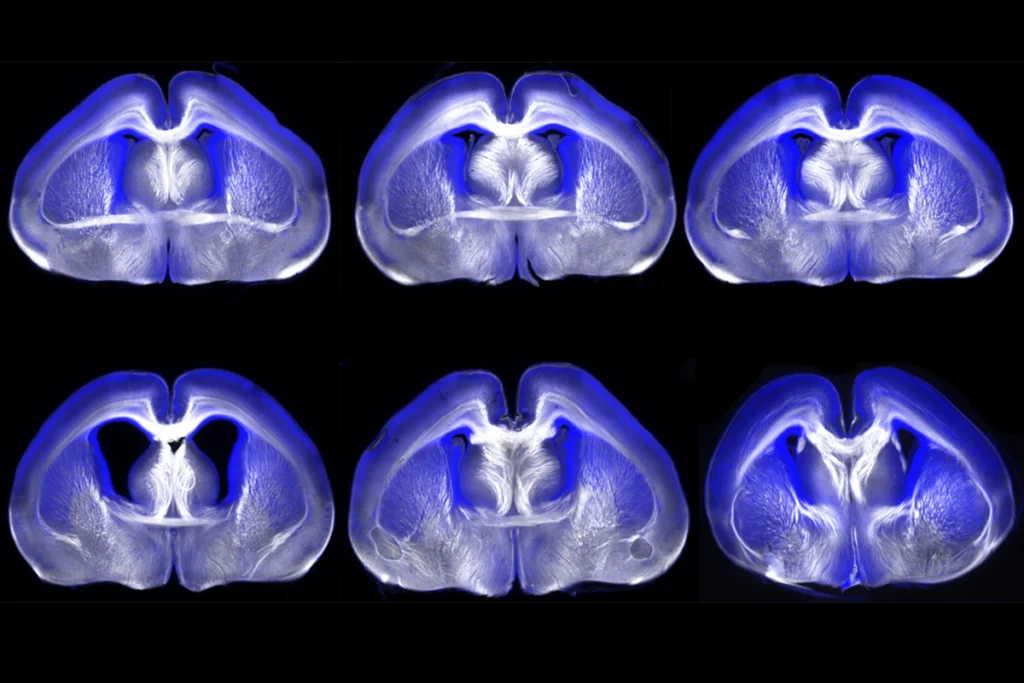

lthough Rett syndrome mainly impacts girls and women, and clinical trials were limited to that population, the label for Daybue includes both male and female patients aged 2 and up. The company announced Monday that the drug will be available for commercial sale by the end of April.That will be the beginning of a new journey for trofinetide — as Spectrum previously reported, the molecule was developed in the early 2000s at the University of Auckland in New Zealand and then trialed for Rett syndrome in 2012 after basic research showed IGF-1 peptide ameliorates symptoms in a Rett mouse model. Neuren will be responsible for submitting the drug for approval outside of North America, though the company has not indicated when it might begin that process.

Acadia anticipates that there are about 4,500 people with a Rett syndrome diagnosis in the United States. Acadia has said the list price is $21.10 per milliliter, and the drug is dosed according to the person’s weight and given twice a day. The company says payers will see an “average net realized cost” of about $375,000 per year per person, the majority of which will be covered through Medicaid or commercial insurance. Acadia has formed a patient assistance program for those who need financial help.

In the full study, results showed a statistically significant improvement on the two primary endpoints of the trial, measured by the Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire and the Clinical Global Impression Scale-Improvement.

Some have been waiting longer than Zoey for the drug. The advocacy group International Rett Syndrome Foundation, which contributed nearly $2 million to the development of Daybue, called the approval “truly a historic day,” and Girl Power 2 Cure put out a statement thanking Acadia.

The excitement is understandable given the dearth of treatments for Rett, but those who take it will need to wrestle with the gastrointestinal side effects seen in the trials.

I

But it was exactly this issue that forced Zoey out of the trial, Adair says. Although constipation is a common issue with Rett syndrome, Daybue swung her daughter in the opposite direction, and it was bad enough for Zoey to miss school, even while taking an antidiarrheal.

The good news is that it’s likely that Daybue is “just the beginning” of Rett treatments — as the International Rett Syndrome Foundation hopes — and indeed there is already another drug in phase 3 development for Rett syndrome. Sponsored by Anavex Life Sciences, the drug is called blarcamesine, or ANAVEX 2-73, and results from its initial phase 3 trial of 36 adult participants looked promising, showing improvement in 72.2 percent of participants (38.5 percent of participants on placebo improved), as measured by the Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire. A separate phase 3 trial in children is ongoing.

Given that Rett is caused by mutations in a single gene, MECP2, the syndrome is a viable candidate for gene therapy and gene editing. Neurogene Inc. is planning a clinical trial for gene therapy in the U.S. in 2023, and Taysha Gene Therapies is recruiting in Canada for a gene therapy trial, which would be the first ever for Rett syndrome. In these instances, the goal is not just to ameliorate Rett’s symptoms but to aim for a cure, and that is why “people have been looking forward” to gene therapy for a long time, says David Lieberman, a neurologist at Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts.

Acadia itself is also looking to improve its offerings for Rett. Last year, the company formed a partnership with Stoke Therapeutics, paying $60 million up front to access Stoke’s antisense oligonucleotide capabilities, aimed at treating Rett syndrome, SYNGAP1 syndrome and an undisclosed neurodevelopmental condition.

Trying to modify Rett will be harder than treating symptoms. Reprogramming genes to make the right amount of a missing protein is complicated work: Too little MECP2 leads to Rett syndrome, but too much can lead to MECP2 duplication disorder. “You have this tight little window in which you want to increase protein,” says Bishop, “but not too much.” Bishop thinks it would be great if Daybue was not the only option for Rett syndrome treatment in the future, but right now the “disease-modifying approaches” are still “very, very early” in the process.

But the upside is also much greater. Adair says she continues to hold out hope for gene therapy and treatments that can fix the “root cause” of Rett syndrome for her daughter Zoey and others. “I’m a little more hopeful about those things,” she says. “But in the meantime, I think it’s good that there’s another drug that can help some girls. I think that’s worthwhile.”

W

The Spinraza approval, Bishop says, felt like a “once-in-a-lifetime experience.” But it also “changed everything” about the landscape for SMA. Now there are two other approved drugs for the condition, including a gene-therapy product. The attention — and validation — that comes with an approval can make a big difference for funding and drug development. It’s likely something similar will happen with Rett syndrome and its community, she says.

But she also takes pride in the fact that Spinraza is helping people. SMA is a neurodegenerative disease that was the No. 1 genetic killer of children under 2 years of age. Since Spinraza was approved, more than 13,000 people worldwide have been treated with the drug. And among children treated in infancy before symptoms arise, some who would have otherwise died are not only still alive but walking.

Of course, there are adults with SMA and adults with Rett syndrome, and they also benefit from the drugs approved for their condition — a fact not lost on Bishop. “But they’re both childhood-onset disorders,” she says, and to her that expands the cruelty of it, because they affect “not only the children, but their whole families.”

Explore more from The Transmitter

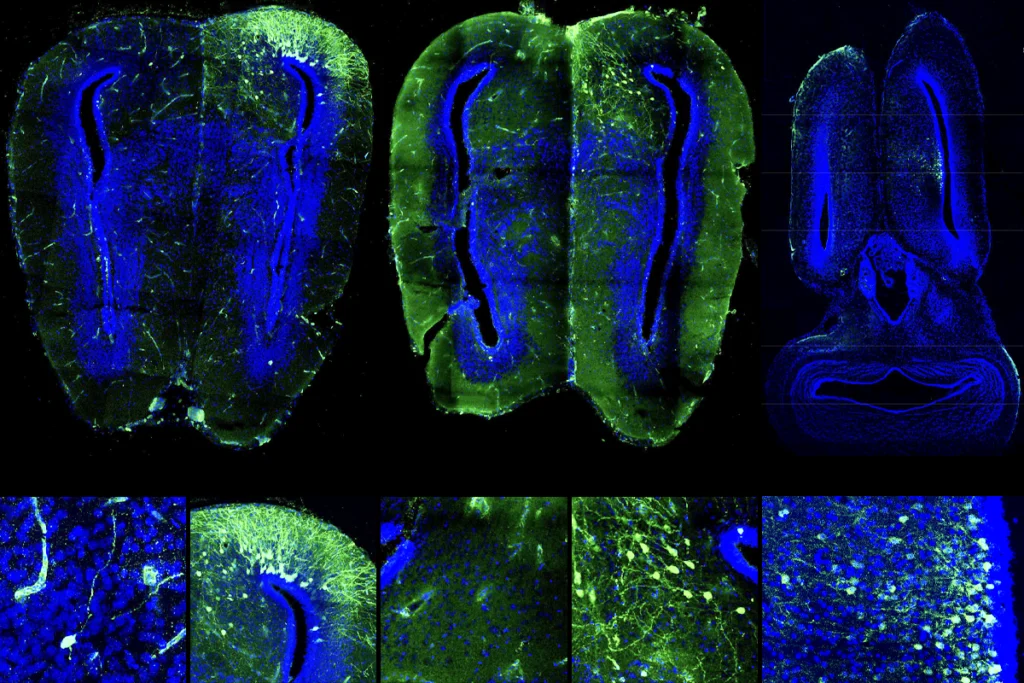

New genetic tools usher amphibian neuroscience research into modern age