THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Patterns of gene expression in the brain vary dramatically between male and female mice, according to unpublished results presented yesterday at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago.

The findings highlight the hazards of using only one mouse strain — or one sex — when studying complex disorders.

“The power of mouse genetics is that any one inbred strain allows you to do reproducible experiments on multiple mice,” says Richard Nowakowski, Randolph L. Rill Professor and Chair of Biomedical Sciences at Florida State University in Tallahassee, who presented the work. “But the disadvantage is that this is like doing an experiment on one person over and over again.”

Studying both sexes in many strains of mice may help to clarify the reasons for the skewed sex ratios seen in a number of neuropsychiatric conditions, including autism. Researchers have historically included only male mice in their studies on autism, but last year, the National Institutes of Health began requiring them to include animals of both sexes.

“To understand autism, we have to understand why boys are so much more likely to be affected than girls,” says Jason Lerch, a scientist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, who was not involved in the new work. “Having an understanding of which genes are differentially expressed will give us important hints about the origin of these sex differences.”

Powerful patterns:

Nowakowski and his colleagues studied six strains of mice, including the widely used C57BL/6J and 129S1/SvlmJ strains, which are commonly used in autism research. When the mice were 3 months old, the researchers dissected out the mice’s hippocampus — a seahorse-shaped brain structure involved in learning and memory — and assessed gene expression in the region.

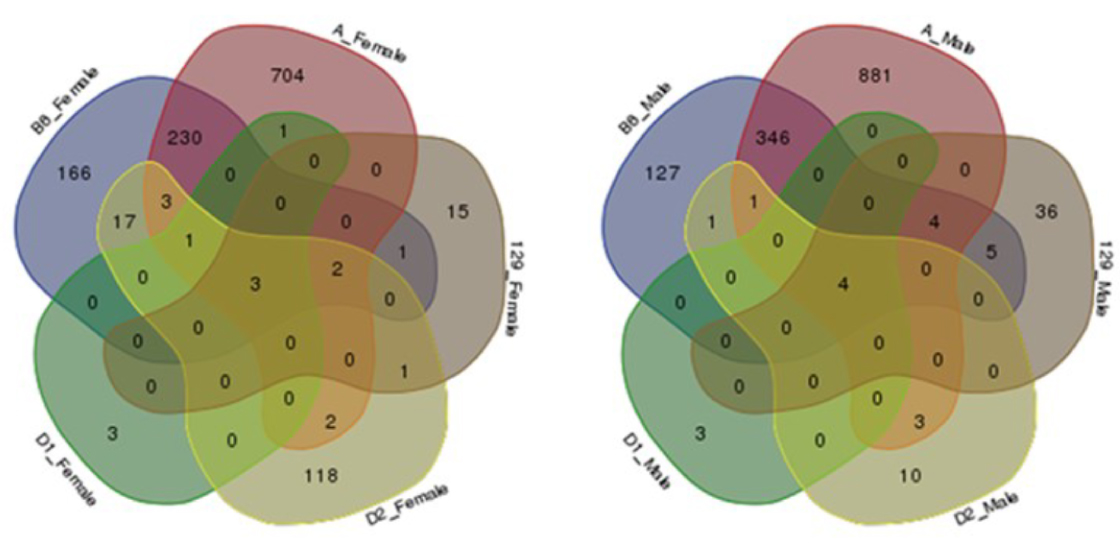

Male and female mice from all six strains show differential expression of a dozen genes, eight of which reside on the X chromosome. But the expression of roughly 2,000 additional genes spanning all 20 mouse chromosomes differs between males and females in a strain-specific way, the researchers found.

C57BL/6J mice, for example, have roughly equal numbers of genes that are expressed at higher levels in either males or females. By contrast, roughly 89 percent of genes in DBA/2J mice, another popular strain, are more highly expressed in females than in males.

The researchers then looked at networks of genes implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, which affects roughly twice as many women as men. Of the 32 genes the researchers looked at, 24 are more highly expressed in female mice than in males, they found. Only four genes are more highly expressed in male mice than in females, and all four are known to be protective factors for Alzheimer’s, Nowakowski says.

One of the genes encodes the calcium channel CACNA1C, which is also implicated in autism, and protects mice from memory loss. Another gene, which encodes low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), prevents the buildup of glucose in neurons.

The researchers then looked at gene expression in 5xFAD mice — a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease — and found that male and female mice again differ dramatically.

Although the findings are preliminary, they reinforce the notion that scientists should study both sexes. This is especially relevant in the field of autism, in which mounting evidence points to a protective factor in girls.

“A lot of good science can be and has been done in mice of one sex,” Lerch says. “The extra work of including mice of both sexes will not usually change the results of a study, but when it does, it can help unlock the mystery of the skewed sex ratios in autism and hopefully provide important mechanistic insights into the disorder.”

For more reports from the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.