Clinical research: Studies add to confusion over gut-autism link

People who have severe gastrointestinal problems during childhood are no more likely to be on the autism spectrum than are healthy controls, a study reported 21 March in Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology.

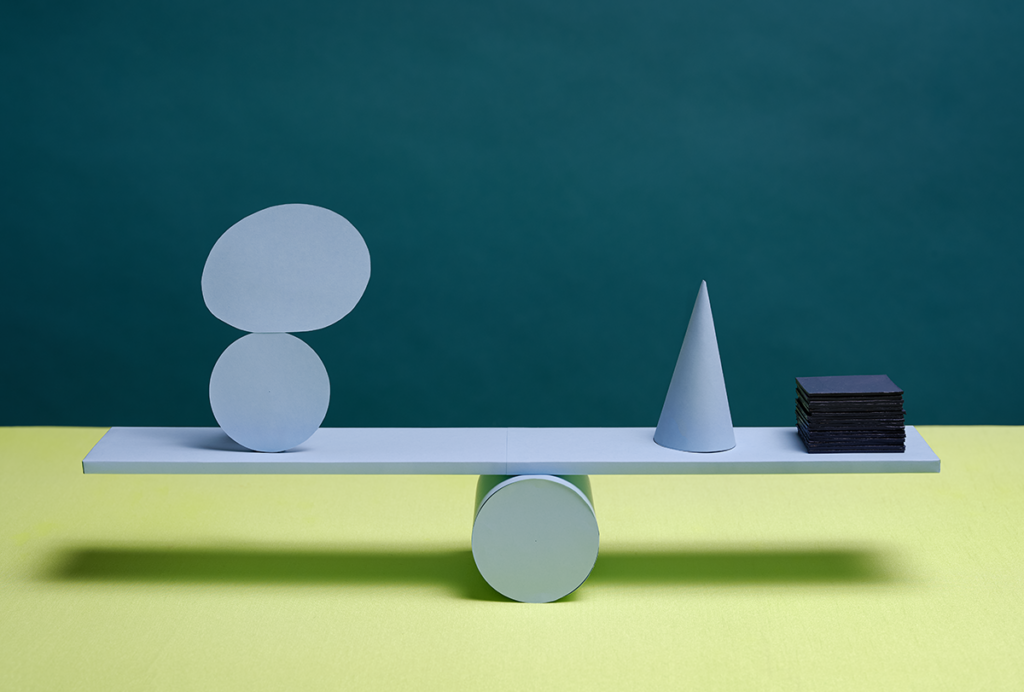

Tummy troubles: Children with severe autism have more gastrointestinal problems, such as constipation and diarrhea, than those with milder autism symptoms.

In the general population, people who have severe gastrointestinal problems during childhood are no more likely to have autism symptoms than are healthy controls, researchers reported in a study slated for the May issue of Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology1.

However, children with severe autism have more gastrointestinal complaints than those with milder autism symptoms, according to a smaller study published in March in BMC Gastroenterology2.

The contradictory results leave unresolved whether gastrointestinal symptoms are an inherent feature of autism spectrum disorders.

Studies have reported a high incidence of gastrointestinal problems — such as constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain or bloating, reflux or vomiting — in children who have autism.

A January study suggested that the gut can actually shape behavior: Mice with fewer gut bacteria than controls are more hyperactive and more likely to take risks.

The first new study screened 804 young adults whose mothers had been recruited as part of a large ongoing study of Australian pregnancies. The participants answered questions on the Autism Spectrum Quotient — a self-reporting survey that gauges the level of autism-like symptoms. Individuals who had gastrointestinal symptoms that required medical attention between 1 and 5 years of age did not have more autism-like symptoms at age 20, the study found.

If gastrointestinal symptoms and autism spectrum disorders had a common origin — or if gut problems led to autism — there would be an association between the two disorders in a group of that size, the researchers note.

Still, the second study found that children with autism who score higher on a measure of gastrointestinal symptoms have more severe features of autism, based on the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist. This study is much smaller, however, with only 58 children who have autism and 39 controls.

Taken together, the two studies present inconclusive results on the link between gastrointestinal problems and autism, but suggest that more large-scale studies in individuals with autism are needed.

References:

Explore more from The Transmitter

How to explore your scientific values and develop a vision for your field