THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Gene expression patterns in the brains of people with autism are similar to those of people who have schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, according to a large study of postmortem brain tissue1. The findings appear today in Science.

All three conditions show an activation of genes in star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes, and suppression of genes that function at synapses, the junctions between neurons. The autism brains also show a unique increase in the expression of genes specific to immune cells called microglia.

“This study demonstrates for the first time that [gene expression] can be used to robustly define cross-disorder phenotypes that are shared and distinct,” says lead investigator Daniel Geschwind, professor of neurology, psychiatry and human genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles. “And these phenotypes are related to the molecular and cellular pathways that likely have gone awry.”

People who have one of these conditions may have features in common, such as language problems, irritability and aggression. They also share certain genetic variants that raise the risk of the conditions.

The new work shows that the overlap among risk variants is related to the commonality in their gene expression patterns. This hints that the variants raise risk in part by turning on or off certain sets of genes in the brain.

“We’re seeing all these studies coming out finding links between genetic variants and psychiatric [conditions], but how do we go from genetic risk to mechanisms?” says Emma Meaburn, senior lecturer of psychological sciences at Birkbeck University of London, who was not involved in the study. “This paper begins to fill that gap.”

Similar signatures:

In 2011, Geschwind’s team characterized gene expression in postmortem brain tissue from 19 individuals with autism and 17 controls. The new work, which incorporates datasets from nine other studies, expands that analysis to 50 people with autism, 159 with schizophrenia, 94 with bipolar disorder, 87 with depression, 17 with alcoholism and 293 controls. All of the tissue came from the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer.

The researchers found that the gene expression signatures in the autism brains overlap with those of both the schizophrenia and bipolar disorder brains. They confirmed this result in independent sets of brain samples from 24 people with autism, 315 with schizophrenia and 94 with bipolar disorder.

By contrast, none of the patterns common to autism, schizophrenia and bipolar overlap with those of alcoholism or those seen in gut samples from 197 people with inflammatory bowel disease — suggesting that the signatures do not reflect poor overall health and are specific to the brain.

In 2016, a different team also found that autism shares a gene expression signature with schizophrenia. Those researchers found no overlap with bipolar disorder. However, their study involved fewer brains — about 30 for each of the conditions — so they might have missed a statistically significant link, says Dan Arking, associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Arking led the 2016 study but was not involved in the new work.

Variant links:

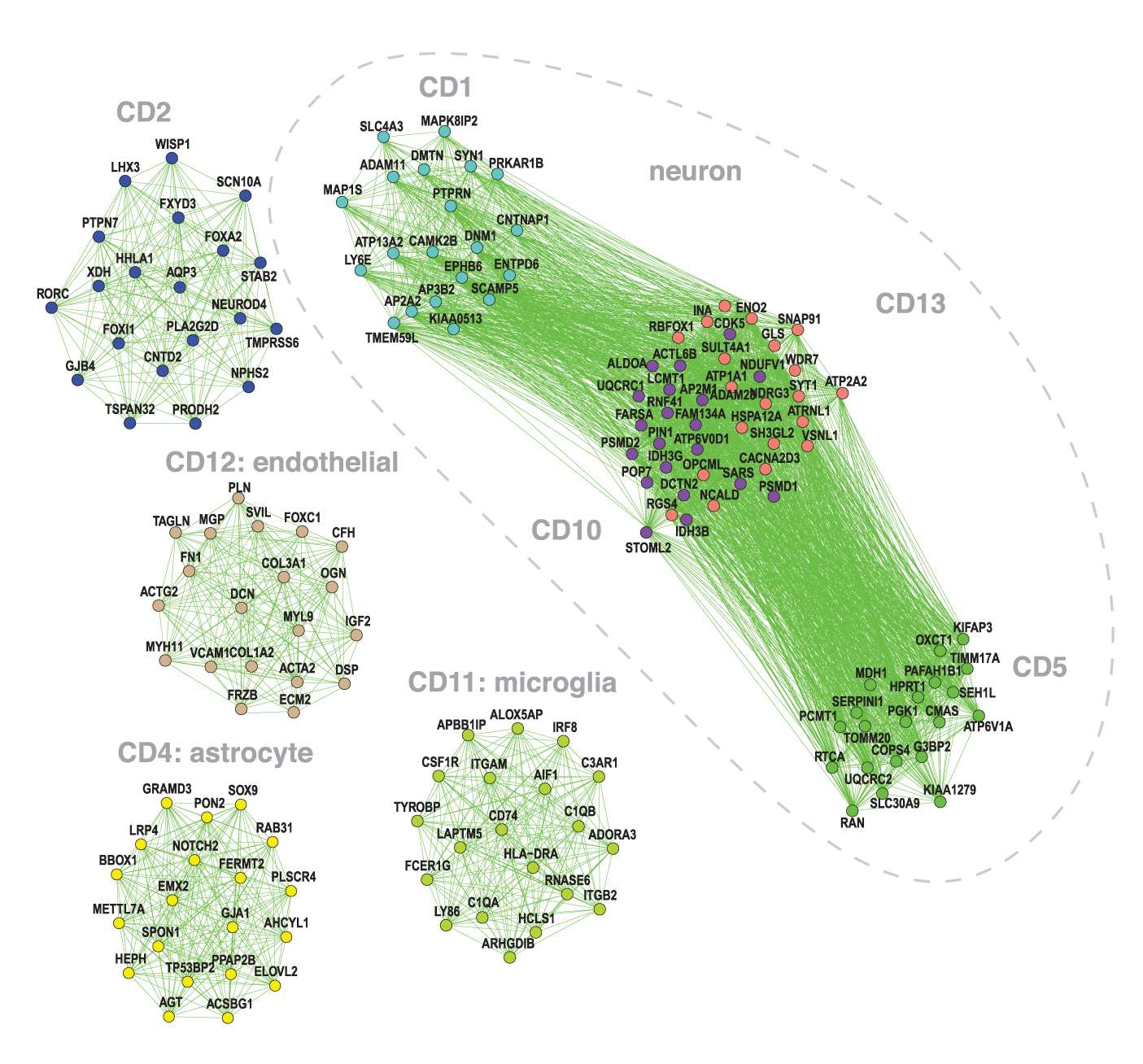

To home in on molecular pathways, the researchers grouped genes into ‘modules’ that show similar rises and dips across the brains. Each of these modules comprises genes specific to a cell type or to a function, such as communication between neurons.

The analysis revealed that autism, schizophrenia and bipolar brains show low levels of gene expression in three modules characteristic of neurons.

Two of these modules are important for neuronal communication; the other one is involved in the function of mitochondria, which generate energy for cells. All three conditions also show an uptick in the expression of genes in an ‘astrocyte’ module.

These shared patterns may spring from a set of DNA variants common to all three conditions.

To explore this possibility, the team gathered data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which reveal common variants — those present in more than 1 percent of the population — associated with the conditions. (For autism, the researchers relied on an as-yet-unpublished GWAS analysis of a Danish cohort that includes 8,605 people with autism and 19,526 controls.)

For each pair of psychiatric conditions, they found a strong correlation between the degree of overlap among DNA variants and the extent of overlap in gene expression signatures.

Common variants linked to autism and schizophrenia tend to pop up in the three neuronal modules. Genes known to harbor spontaneous mutations linked to these conditions also fall within one of the synapse modules.

These results suggest that many variants linked to autism and schizophrenia dampen the expression of genes involved in signaling at synapses.

“This is starting to pinpoint some of the common pathways,” says Tomasz Nowakowski, assistant professor of anatomy at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

Microglia machines:

Autism brains alone show a spike in the expression of genes associated with microglia, the researchers found.

That finding is somewhat surprising, because microglia have also been implicated in schizophrenia, says Stephan Sanders, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

Characterizing the gene expression patterns of microglia and other individual brain cells, rather than the patterns in a chunk of tissue, might lead to more refined results, says Nowakowski, who has studied gene expression in single cells in the developing human brain2.

Geschwind and his team are exploring how the gene expression patterns relate to neuronal activity. They are also studying whether these patterns can be replicated in cultured neurons and in microglia carrying mutations tied to each of the conditions.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.