Funding the epigenome

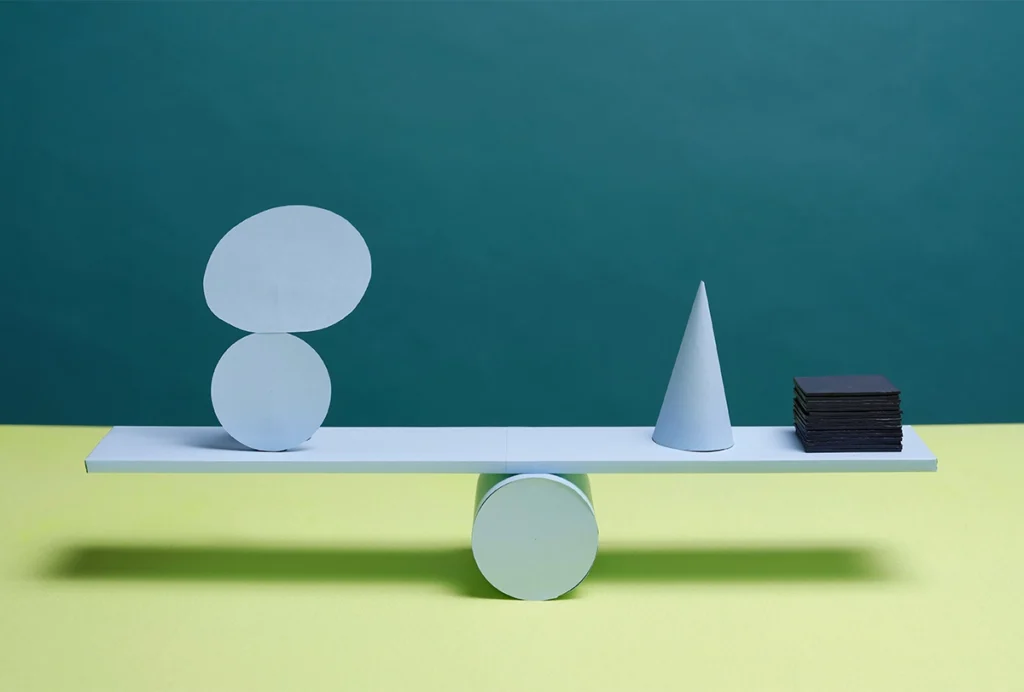

The more we learn about genes, the more obvious it becomes that disease often transcends genetics, and that the real defect may in fact be in how the gene is regulated or tweaked ― what we call epigenetics.

d2f7054c-367d-d6c4-edc3-7c8a6a5416ee.jpg

The more we learn about genes, the more obvious it becomes that disease often transcends genetics, and that the real defect may in fact be in how the gene is regulated or tweaked ― what we call epigenetics.

One particularly clever way I’ve heard it put is that if genetics involves unraveling the letters of the code, epigenetics is the study of the fonts and the colors in which those letters are written.

A few weeks ago, when the foundation hosted a workshop on epigenetics, I heard repeatedly that although everyone now realizes the importance of epigenetics, money is scarce.

Well, thatʼs about to change.

Last month, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that it would invest more than $190 million over the next five years on epigenomics ― the analysis of epigenetic changes across many genes.

Among other goals, the NIH hopes the new program will help develop new technologies to analyze epigenetic changes in a single cell and to image epigenetic activity in living organisms. Any epigenome maps that result from the projects would be freely available to other researchers.

Aging, environmental chemicals, drugs and diet can all trigger epigenetic changes that may turn on or off certain genes and alter the risk of developing certain diseases. The NIH has a neat illustration of how this happens.

For example, children born to mothers who did not get adequate nutrition during pregnancy are more likely to develop type-2 diabetes and coronary heart disease later in life.

Although they donʼt change the genetic sequence, some epigenetic changes can still be passed on from generation to generation ― like a color copy of the genes, if you will, rather than one thatʼs merely black and white.

Explore more from The Transmitter

How to explore your scientific values and develop a vision for your field